No products in the cart.

Aaron Perry

[Biochar Science with Dr. David Laird] In this episode Dr. David Laird, PhD, discusses the science of biochar. Biochar is a form of charcoal that occurs naturally as a result of forest fire, and that is produced in a controlled combustion called pyrolysis. Biochar is increasingly recognized as essential to many soil-building processes, and is hailed for its unique carbon sequestration properties.

Biochar is like a sponge of sorts, with small, cavernous spaces throughout its structure that provide habitat for soil microbiology and that provide water absorption and retention advantages to soils. It is estimated that between 10% and 50% of the carbon in natural soils is char. With chemical properties between those of graphite and biopolymers (all forms of carbon), biochar has a “half-life” of 100s if not 1000s of years; meaning that the carbon absorbed from the atmosphere by the plants and trees that are made into char remains in the ground and doesn’t release back into the atmosphere for a relatively long time. This is the reason that the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and other leading scientific authorities recognize biochar as a key to climate stabilization.

Dr. Laird discusses how evolving policy alongside evolving carbon credit markets are helping to transform the economic and ecological landscapes for farmers, ranchers, foresters, and other land-stewards who can apply biochar to their soils. With the correct incentives and market drivers, biochar has the potential to deliver one gigaton of net carbon reduction annually in the United States and 10 gigatons world-wide.

David Laird received a PhD in agronomy from Iowa State University in 1987. He is currently founder and president of N-Sense Inc, an agrotechnology company and professor emeritus at Iowa State University. As a professor he mentored 20 M.S. and Ph.D. students. He is author or co-author of over 157 refereed journal articles and book chapters related to biochar, bioenergy, clay mineralogy, clay surface chemistry and environmental science. His publications have been cited over 20,000 times and his h-index is 60 (Google Scholar). Previously he served as editor of Geoderma, associate editor for Soil Science Society of America Journal and Clays and Clay Minerals and as President and vice-president of the Clay Minerals Society. He is a fellow in the American Society of Agronomy and the Soil Science Society of America.

Video – David Laird: Biochar for Carbon-Negative Energy

International Biochar Initiative

Biochar Research Network Act of 2022 – SB4895 / HB8596

Episode 120 – Rowdy Yeatts, Founder, High Plains Biochar

Episode 91 – Finean Makepeace, Co-Producer, Kiss the Ground Movie

Episode 89 – Dr. Yichao Rui, Chief Soil Scientist, Rodale Institute

Episode 70 – Jeff Moyer, CEO, Rodale Institute

(Automatically generated transcript for search engine optimization and reference purposes – grammatical and spelling errors may exist.)

Welcome to the YonEarth Community Podcast. I’m your host, Aaron William Perry. And today

we are visiting with Biochar Expert and Professor Emeritus David Laird. Hey David, how you doing?

I’m doing great Aaron, how are you?

Doing really well and really excited for our conversation today. We’ve got so much to cover

that relates to regenerative agriculture, carbon sequestration, food production yield improvements

and other topics related to Biochar and really look forward to hearing from you on this topic.

Well, thanks. Thanks for inviting me. I appreciate you being here and opportunity to meet with you and with your audience.

David Laird received a PhD in Agronomy from Iowa State University in 1987. He is currently founder and president of NSENC Inc.

and Agrotechnology Company and Professor Emeritus at Iowa State University. As a professor, he mentored 20 Masters in PhD students.

He is author and co-author of over 157 refereed journal articles and book chapters related to biochar, bioenergy, clay mineralogy, clay surface chemistry and environmental science. His publications have been cited over 20,000 times and his age index is 60.

You can find information about that on Google Scholar. Previously, he served as editor of Geoderma, associate editor for Soil Science Society of America, Journal and Clay’s and Clay Minerals and as president and vice president of the Clay Minerals Society.

He is a fellow in the American Society of Agronomy and the Soil Science Society of America. David, it’s welcome to the show. It’s so great to have this opportunity to visit with you and I guess to kick things right off and kind of get our hands right down into the soil of the matter.

Let me ask you what is biochar and why is this important right now?

Thanks Aaron. Biochar is charcoal. For those of you not familiar with it, but it’s not the charcoal briquettes that you get the bag and put in your barbecue.

Those have actually have a number of additives in them. They actually physically mix in clay and starch and sometimes they put in accelerants to speed up the burning.

You don’t want to put a charcoal briquette on your garden. That would not necessarily be wise. But biochar is more like the charcoal you find in a campfire.

The black char that is the unburned residue of the wood in your campfire. But biochar can also be made from virtually any source of biological materials.

It can be made from corn stover or it could be made from a switchgrass or a wheat straw or any number of different biological materials.

You can put it in what’s known as a pyrolyzer and turn it into biochar. A pyrolyzer is a little different from a campfire and a campfire depends on how good your campfire is.

But 95% of everything goes up in smoke. In a pyrolyzer, it’s sort of like an oven, but it’s an oven in which you restrict the amount of oxygen that gets in there.

Ideally, heat the biomass, the wood or the wheat straw up with little or no oxygen present. And as it heats up, it thermally decomposes and you get some gases, smoke-like material coming off the top.

And the solid residue is the char. And that char, it’s much more efficient in a pyrolyzer to produce the char than a campfire or something like that.

And it’s a material that you find naturally in soils. You find, well, I’m in Iowa, right? And we have a legacy here of like 10,000 years of purifiers.

Every time the purifier came roaring through a small amount of char was left behind and it got incorporated into our soils. Some estimates are that, oh, I don’t know, between 10 and 50% of the carbon that is naturally in the soil is char.

The pyrogenic it came from those wildfires. And this is true all over the world. So char is very much a natural thing. What’s new, oh, and let me add that there is also a historic legacy of using char in soils.

A lot of the new science began when a number of people discovered the so-called terapreta soils down in the Amazon.

And so if you go down the Amazon jungle, you have, this is a really cool story. You have this really incredible biome down there, greatest biome on the planet, right?

But underneath that biome, the soils are awful. Soils evolve with time and with weather. And down in the tropics, they had intense leaching. And so you’ve got these soils that deep red soils, they have low activity place, they don’t hold nutrients, right?

And in some cases those tropical soils can hard set turn into stone if you dry them out. So that’s a terrible so. And yet it supports this incredible biome.

And that has down there and the thing that struck me was that all the roots are right near the surface.

So leaf falls in the jungle and the leaf has nutrients and it has potassium, phosphorus, nitrogen and so on. And as soon as it hits the ground, the fungi are eating away at that leaf.

And resize all those nutrients back into the bio. Well, the emer Indians who lived down in the Amazon, you can imagine if you’re trying to cut down a tree, make a garden with a stone axe, that’s a lot of work.

Anyhow, they figured out that they could basically dig a trench and put woody biomass in there, burn it, turn it into charcoal and incorporate that into the soil.

And it would improve the quality of those soils, make them hold nutrients and water better. It would raise the pH, make them less acidic.

And when it soils, one of the reasons the roots don’t go deep in the Amazon is the soils are acidic.

It’s just too acidic for those roots to start eating holes in the roots.

If you raise the pH, but putting char on ash and probably manures of various kind, you know, suddenly the roots can go deeper into that soil.

So today, 500 years after that emer Indian population died out, they’ve left behind this incredible legacy of these terra credit soils.

Anthrogenic soils, they’re human made soils and they’re still the prize horticultural cropping soils down along the Amazon.

They’re in small patches, they’re not big continuous areas, maybe as much as 10 hectares in a few places, but most of the patches are much smaller than that.

And you know, discovery of these terra credit soils ignited interest in biochar about the mid 2000s.

Before that, if you look at the number of citations around the word biochar, there’s essentially zero up until about 2007, and since then it’s quite exponential growth.

And it was really that discovery or not so much the discovery, but the recognition that the terra credit soils were anthropogenic and that the use of charcoal and soils could have a real positive impact on soil quality, soil health and increase resilience of cropping systems that really sparked the interest.

So interesting and can you explain to us a little further how the biochar enhances the soil quality, what’s unique about biochar and what’s it actually doing within the soil structure that wouldn’t otherwise be there.

Okay, so soils are a mixture of minerals, sand size, silt size, clay size minerals and organic matter and core space holds between those water, air and life biology.

Microrganisms, bacteria, fungi, tinomyces, roots, arthropods, all kinds of earthworms, right.

It’s that interplay between the geology, the mineralogy and the atmosphere and rain and sunlight and biology, the plants growing.

All of it occurs at this interface of our earth’s surface, the soil and soils evolve with time.

And a big piece of that is the organic matter that’s there.

If you take all the organic matter, the black, the humus out of the soil, the soils tend to consolidate, they get hard.

Roots can’t go through them or they grow sideways and they don’t hold water, they don’t hold nutrients as well.

So what soil organic matter does is to sort of fluff up the soil to make more core spaces between the mineral particles and to glue those particles together to make what we call aggregates.

Or little clumps of soil and the organic matter is this immense reservoir of nutrients.

The nitrogen is in the organic matter, sulfur is in there and then organic matter along with the clays have the ability to hold other nutrients like potassium and phosphorus.

Alright, so that’s sort of the natural cycle.

And okay, another part of that concept is that every year, plants grow, they die, the leaves fall to the ground.

And some of that leaf carbon gets built into new organic matter and much of it goes back to the atmosphere as CO2.

It turns out that biochar char, sort of generically we can use the word char, is very similar to that stabilized human material, but it’s also a little different.

And as I mentioned earlier, there’s a lot of char in our soils naturally, legacy of wildfires.

Char is lightweight, if you were picked up a piece of charcoal, it’s very light, right?

And the reason it’s so light is that it’s full of holes.

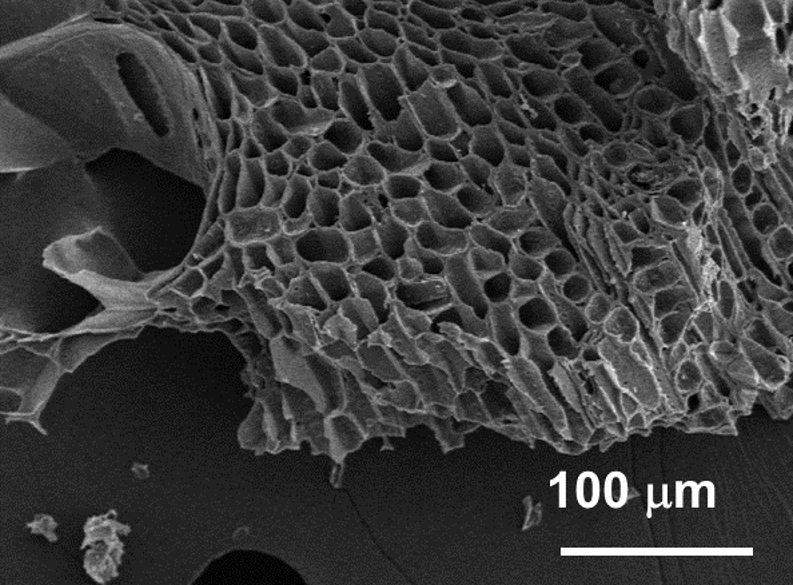

If you have an electron micrograph, an SEM, a scanning electron micrograph, you can see these basically 10 micron holes.

It’s significantly smaller than a human hair.

It’s too small to actually see with your naked eye, but they’re there.

And it’s just this honeycomb full of holes and those holes hold water that plants can use.

The charcoal also has a lot of surface area that all those holes, there’s little surfaces in there.

And those surfaces become habitat for microorganisms, bacteria, fungi, and so on.

They also function to absorb what we call dissolved organic matter.

As a leaf is decomposing, microbes are chewing on it.

Some of what they’re doing is they’re using that leaf for their own metabolism.

So they’re exhaling CO2 that goes to the atmosphere.

But they’re also excreting what we call dissolved organic matter.

So fragments of biopolymers is how I would put it.

But they’re just fragments of molecules.

Organic, they might be a couple of sugar molecules hung together or some amino acids and other types of organic compounds.

And those end up being absorbed on the surfaces of the char.

And when they’re absorbed there, they are stabilized, reducing the rate at which microbes turn them into CO2.

So what is the char doing in the soil?

Well, it’s fluffing up the soil.

It’s putting more pore space in there.

With more pore space, roots can move through the soil easier.

With more pore space, you can hold more water for the plant.

And you allow better air-ish movement of air and water and roots through that soil.

Plus, in a chemical sense, it’s holding the absorbing this humic material,

helping to stabilize and help them to build the biological humic material in addition to the carbon itself.

And it’s providing habitat for the microorganisms in soils that do all this recycling.

So it functions in both the physical, chemical, and biological sense to enhance the soil quality or soil health

as we like to say.

Make it a better rooting environment.

Yeah, I’ve heard that biochar, when we add biochar into the soils, it’s almost like creating condominium complexes for the organisms.

And the life there is that? Is that an apt analogy in your opinion?

Sure, sure.

You make it a better habitat for the microorganisms.

I think that would be a more technical way of putting it.

Sure, sure.

It makes it, but it also will change the population dynamics, too.

So you might get different types of organisms living in there.

Hopefully, the beneficial ones rather than the pathological ones.

Is that an issue when you’re introducing the biochar into the soil that you may or may not get the kinds of organism populations that you’re hoping for?

I think that’s a frontier in science that needs more research.

Let’s put it that way.

I have not seen evidence of that.

Let me just say that.

That’s speculative.

We certainly know it influences the population dynamics, but we don’t know enough to say how that impacts functioning of the soil.

Let me ask this just to get, sorry, go ahead, David.

I don’t just say by functioning.

I mean nutrient cycling, stabilization, all the processes that can symbiotically support plant life.

Okay.

Yeah, great.

Let me ask just from a technical description point of view,

maybe using too many terms that might not be familiar to some of our audience.

What is it about the paralysis process that is turning the woody biomass or other agricultural residues or other biological materials into biochar instead of what they would turn to if there was ambient regular levels of oxygen available for the combustion?

Sure.

So if you look at plant tissue, a leaf, right?

It’s a mixture of a number of different molecules, and a lot of it is what we call cellulose.

Cellulose is a lot of sugar molecules strung together like a string of beads, but it also has proteins in it.

And proteins are sort of more globular, and they’ve got strings of amino acids.

And amino acids have nitrogen in them and sulfur and some other things.

And there are other nucleic acids like DNA, right?

There’s all sorts of, what we would call biopolymers in that leaf tissue.

And all of that, all of those biopolymers are basically lunch for soil microorganisms.

That’s where their dinner comes from, and that’s what they eat.

And so if a leaf falls on the surface of the soil, the microorganisms are going to go after it.

And we say that the half-life of the carbon that is in that leaf, and typically maybe 40-41% of the leaf mass is carbon.

But the half-life, the amount of time it takes for the carbon in that leaf, once it hits the soil surface,

to go back up into the atmosphere, for half of it to go back into it, is measuring a couple of months.

And this means that after 3, 4, 5 years, 99% of the carbon that was in that leaf is back in the atmosphere of CO2.

And it’s because the leaf is lunch for the microbes.

If you take that same leaf, and you put it in a pyrolyzer, you heat it up to about 500 degrees centigrade.

It thermally decomposes, and you’re going to have this smoky material coming off the top.

But you’ll be left with the char, and the char is chemically different.

It’s dominated by carbon. It can be as much as some percent carbon.

Sometimes it’s lesser amounts.

Also has some ash mixed in with it.

The ash is mostly oxides and minerals like potassium, phosphorus, calcium, magnesium, and carbonates.

So inorganic carbon forms will be part of that ash.

So if you have a high ash biomass, a high ash leaf, right, then you’ll get more ash less carbon.

If you have a biomass that has a lot of organic matter, very little ash in it, then you’re going to get a carbon-rich char.

And that typically comes with plain wood, right, if you’re really carbon-rich char.

Part of that chemistry that goes on during that paralysis reaction is that the carbon molecule will start bonding to each other.

And they form what we call condensed aromatic carbon.

Now, everybody knows that a diamond, right, is carbon.

And if I took a diamond and put it in the soil, it’s going to be there for millions of years.

Now, that’s a hard way to sequester carbon, or an expensive way to sequester carbon.

But you all know that the chemical form of carbon matters.

If it’s in a diamond structure, it’s essentially inert.

No microorganisms is ever going to touch it.

We can also have carbon in the form of what’s called graphite, pencil lead is graphite.

And graphite is also, for all intensive purposes, inert to microorganisms.

They can’t chew on it, they can’t eat it.

It’s not digestible for microorganisms.

Well, char is somewhere between graphite and these biopolymers that are in the leaf.

It’s probably a little closer to the graphite side.

It has a structure of carbon-carbon bonds.

And some of them are aromatic.

They have a…

I’m trying not to get into organic chemistry here, but…

For those chemists out there, you know what a benzene ring is.

You’ve got six carbons in a circle, and you’ve got that circle in the middle, which implies that you’ve got these pi electrons zinging around, making aromatic bonds.

Well, that’s what char is.

It has a lot of that in it.

And that means that it is not very digestible to the microorganisms.

It’s not totally inert, like a diamond or graphite, but it’s certainly much more inert than that leaf was.

So, we’re taking a leaf in which 99% of the carbon is going to go back to the atmosphere in a couple of years.

And we’re turning it into biochar and the half-life of the carbon in biochar.

It’s going to vary, but let’s say 500 degrees C, woody biochar is going to be measured in hundreds, if not thousands of years.

So, it is many orders of magnitude more stable, resistant to biological degradation than the original leaf.

And that is the real reason that biochar is a good agent for carbon sequestration.

Because if I let that leaf land on the soil surface in a couple of years, it’s all back in the atmosphere.

I pick that same leaf and turn it into char.

Then I’m going to capture, I don’t know, 50%, maybe 30%, depending on the process I use, the total carbon will be captured in char.

The rest of it’s going to go into the atmosphere of CO2.

But the part that I capture is going to stay in the soil for hundreds of thousands of years.

Yeah, it’s so important. And as we have seen an increase in atmospheric carbon from somewhere around 280 parts per million at the beginning of the industrial revolution now well over 400 parts per million and continuing to move here by year, these kinds of strategies are obviously really critical to climate stabilization.

And I’m curious, from your perspective, how does biochar scale up in such a manner that it can have a meaningful impact on the climate stabilization efforts that we’re hoping will deploy in scale as a human species on the entire planet right now?

Well, that’s an excellent question and we could spend about three hours talking about that topic alone.

The IPCC has said we don’t only have to reduce for dependence on fossil fuels, we got to end it, right.

But we also have to go carbon negative in the second half of the century.

That means we have to be literally pulling CO2 out of the atmosphere, reducing that atmospheric concentration.

If we want to keep global warming at the 1.5 degree C level, and that’s because we’re going to oversh…

We’re on a trajectory, our economy, our global economy is on a trajectory to overshoot the safe zone as it is.

So if we don’t want to get into serious trouble, we’re already seeing these ramifications in terms of all kinds of climate related problems.

Record heat spells, mega hurricanes that accelerate in strength very rapidly, droughts, floods, the whole gamut,

and of course the forest fires that he went out to California, Pacific, with a western half of the U.S. knowns about forest farmers.

And of course, none of these things are simple cause-effect linked to climate change.

You’ve got bark beetles killing trees and you’ve got all sorts of other issues that are compounding, you know, forest management.

But climate change is a piece, an important piece of that, of what’s causing the forest fires, what’s causing the increased probability of flooding or of drought or of other climate extreme events.

So we’ve got to find a way to go carbon and negative, and there are very few options available to go carbon negative.

You’ve probably heard about direct air capture.

So these are big devices that will literally capture CO2 out in the atmosphere, put it in a form, a chemical form that can then be released under and pumped under pressure.

So you’ve now got it in a pipeline of CO2 and then you run that pipeline where you’ve got the right geology and you pump it down into the ground and into some kind of a sandstone or something under the underground where hopefully it stays for indefinite period of time.

It’s really expensive to do and it takes a huge amount of energy to capture that CO2, run a pipeline, pump it underground and so on.

So yes, that’s an effective method, but boy, we can’t afford it.

All the other things and to get that at scale, another thought has been to use what’s called accelerated mineral weathering.

It turns out you can take certain types of silicate rocks that have calcium, magnesium in them, any crush them up so they’re real fine and they’ll react with the CO2 in the atmosphere and make carbonates.

Make limestone white materials and that’s another way we can maybe pull CO2 out of the atmosphere.

Again, that’s fairly expensive to do that.

You got to mine the rock, you got to crush it, you got to spread it out somewhere and look the reaction occur.

So these are certainly options, but they are challenging to implement and they generate no net economic value other than removing the CO2 in the atmosphere.

It’s got to be totally taxpayer funded or some kind of carbon credit funding that drives those mechanisms.

Biochar is a unique option in that it produces value in addition to capturing the carbon.

So another option that I haven’t mentioned is BEX, bioenergy, carbon capture and storage.

And so the classic concept of BEX is that you would put to booty biomass trees and you would burn them, use the heat from the burning to boil water and use the steam to run a steam turbine and generate electricity.

So you’re gaining a value from that, right?

And then the other thing is then from that power plant, you capture the CO2 and you put it in a pipeline and then you pump it underground and BEX systems are considered to be carbon negative and you will find a lot in IPCC reports about BEX.

IPCC is the international panel on climate changes that right that acronym is correct.

Essentially the leading science and scientists from the entire global community looking at all of this from a data driven and peer reviewed standpoint.

Right, and there they say we’ve got to go carbon negative in the second half of the century and they put BEX forward along with this accelerated mineral weathering and direct their capture as options for going carbon negative for pulling the CO2 out of the atmosphere.

So in the case of BEX at least you’re generating value, you’re generating electricity and you’re capturing carbon.

So that’s seen as one of the more promising approaches.

I’m a soil scientist and to be blunt BEX scares me a little bit because I know what happens if you at least on agricultural soils for soils are a little different.

But on agricultural soils if I harvest all that corn stover wheat stover and burn it to generate electricity, I know what’s going to happen in my soil quality.

The organic matter the humus in that soil is going to start to degrade over time.

And now we’ll lose fertility, huh? You’re going to lose, you’re going to lose nutrient water holding capacity nutrient cycling is going to decrease.

You’re going to see the soils consolidate, come harder, more difficult for roots to grow in and ultimately.

If we start harvesting gigatons of residue of our egg soils to remove carbon from the atmosphere, we might remove the carbon from the atmosphere, but we might starve to death.

You don’t want to go down that route.

And we know that already worldwide soils are in decline and have been in decline in large part because of our industrial approach to agriculture.

You really need to look for synergisms that can build soil quality at the same time and that’s the unique thing about biochar.

I can take the crop residue off of a corn field, I can pyrolyze it, generate energy and put the char back on the same field from which I took that residue off of and build soil carbon, soil quality, soil health at the same time.

That’s the win-win-win part of this.

It’s beautiful. It’s beautiful. It’s exciting. Yeah, it’s fabulous, right? What you can remove carbon from the atmosphere at the scene.

You know, by the way, when earlier you were talking about how diamonds and graphite are not bio-available, they don’t get eaten.

I almost wanted to interject with a little joke about when we were back in kindergarten. Some of us tried eating graphite in our pencils, I think.

But, you know, that’s… I don’t think it hurt you. I just went through it.

But, I mean, in order, you know, thinking about the children and thinking about future generations and thinking about the work we can be doing in our lifetimes, the work that you’re doing, David,

you know, what is needed from your perspective to scale up this particular win-win-win solution so that we are addressing climate stability while we are also addressing the nutrient and food production needs of the world?

What do you think we need to see happen in order to scale this?

All right, so I’m going to say we need more research, right? Talk about that later. But we can’t sit around for 30 years or 50 years doing all the perfect research, right?

We’ve got to get going now, right?

And we can do the research while we are going ahead with the development of this.

That perfect getting the way of good, right?

Be the enemy of good, right? We can’t do that.

And nobody said biochar systems are perfect. They’re not. They’ve got issues.

And, you know, just to, you know, put it on the table here.

If we look at the literature, scientific literature, I see many cases where biochar results in a positive yield increase, right?

Well, we’re all happy about it. I see also many cases where there is no net effect of biochar. I put it on and, you know, I’ve got the same yield as before.

And there are some cases where you actually see yield decreases.

Okay. Now, that is not magic. It’s not random.

It is driven by agronomy or the type of crop, the type of soil, the climate, the management system that was used.

And we need to understand from a research perspective that if I use this type of biochar on this soil with this crop and this climate and this management system that I’m going to have a positive outcome.

And if I do it with a different one, I’m going to have a negative outcome. We need to be able to tell the farmers, the land managers, the recipe or the prescription, how to use biochar to get the maximum soil quality, soil health benefit, the maximize your crop yield potential as well.

So that research needs to be done. Okay. But as I said, we can’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good because that’s the perfect, right? When we know all of that, we can hand the prescription to the farmer. This is how to do it.

Well, we’re also going to learn by doing. We’re going to make mistakes and we’re going to, you know, not make those mistakes twice, right? That’s the whole idea. And so we’ll get her to get better and better with time.

So we need to get started in on the practice to scale mile mass to the gigaton level.

I hate to say it, but it’s money. It’s got to be, there’s got to be a net value.

I know a lot of corn farmers here in Iowa and, you know, they’ve got really thin margins, the cost of inputs, you know, equipment, you know, on and on and on.

They can’t just apply biochar because it’s a nice thing to do.

If we want them to end and, and by the way, we’re never going to get there by putting biochar in our backyard garden.

I mean, that’s, you know, that’s a cool thing to do, right? And I did it, right?

But it’s not going to get a gigaton of CO2 out of the atmosphere.

So if we’re scaling it, we’ve got to have biochar applied on corn fields all over the Midwest on, you know,

horticultural crops in California on cotton down in Georgia, Louisiana, and not just in the US, but all over the world.

We’ve got to have an integrated system that gets us to that level.

And, you know, the way the world works is with money. It’s got to be profitable for the farmer to want to apply that biochar.

And there’s really two ways you do that. One, you get an increase in your crop yield, or you get an improvement in your nutrient use efficiency.

So you could put on less fertilizer and get the same yield, right?

Or you get some kind of a subsidy. And that subsidy could be, you know, a tax credit.

It could be a direct subsidy from the government. It could be a carbon credit that is sold on the Chicago Board of Trade.

In some way or another, the profit has to go to the farmer so that the farmer is incentivized to use biochar.

And again, I’ve done the math for corn fields in Iowa.

If we can get Iowa farmers to use biochar on a regular basis, we’re home. We’ve made the home run, right?

And at most, an Iowa farmer could afford to pay somewhere around $50 a ton for the biochar if it’s based on yield improvement.

And that’s it. That’s it. If you look at where the biochar industry is today, they’ll be happy to sell you a ton of biochar for $1,000.

It’s small scale and their markets are niche markets. They’re targeting high value horticultural crops.

You have to put in them an acre of strawberries in California Central Valley.

It’s close to $100,000 in one acre, right? So if you spend a few thousand dollars on biochar, that’s chunk change by comparison to the money that’s being involved in the production of those strawberries.

And you look at a lot of the, you know, orchards and vineyards. Those markets have that high dollar value and can afford invested in biochar, particularly if the biochar improves water use efficiency.

So what’s the big problem out in the Central Valley? It’s water. Yeah. And if I have a 10 or 20% improvement in my water use efficiency by putting biochar on, it’s worth it to me.

If I have a hundred thousand dollar crop out there, right? But if you’re trying to grow corn in Iowa, where your margin is a couple hundred dollars an acre, you can’t afford it.

Yeah. I’m here and from some of our friends and colleagues in the finance world that there’s global demand now for carbon credits coming from biochar with buyers willing to pay well over a hundred dollars a ton, sometimes hundred and fifty dollars a ton.

So it seems to me, because I, you know, I’ve been in this world for 20, 25 years, not as long as you David, but long enough to know that we’ve had decades of folks saying, hey, when the carbon markets come, when the carbon tax or credits come and provide that additional economic signaling, that’s going to be the game changer.

Well, it seems that we are, those days have arrived. They’re here clearly they’re, they’re, they’re nassent, they’re young and have a long way to go. But by golly, it seems that those markets signals are already starting to show up in a manner that can make some very meaningful impact on the micro economics of these farmers.

I absolutely agree with you. We’re starting to see the sale of carbon credits here in the US for biochar. There are water sales in Europe and other parts of the world and they are attracting a high value for those carbon credits, not top dollar.

I heard that in Iceland, I think it’s Iceland. There is a direct air capture system and geological sequestration of seats. They were, they were selling carbon credits for six hundred dollars a ton.

You know, if we were selling biochar carbon credits for six hundred dollars a ton of CO2, let me tell you, I will be applying biochar by the gigaton.

It would have been like that, right?

More realistic, two hundred dollars a ton would be enough to incentivize wide scale and scale of application. And I needed that direction.

We’re quite there, but we’re getting close. But it also means that we have to have industrial scale production of biochar.

Yeah, not going to be doing it on farm and in our backyards. I know that there’s a lot of biochar producers out there that don’t want to hear this.

And if you could sell biochar for a hundred dollars a ton or fifty dollars a ton, how are we going to do that?

And how are we going to process gigatops of biomass in order to get there?

And, you know, quite frankly, it took huge industry, the oil and fossil fuel coal industries to get us in this problem.

And it’s going to take that same scale of operation to get us out of it.

I don’t see it another way.

Is emerging. The opportunity is coming. I’ve been working with Robert Brown at the Iowa State University Bioeconomy Institute and his team and their engineers, they worked on a development of process known as auto thermal fast paralysis.

And it’s a really cool technology because the auto thermal means that it makes its own energy. It doesn’t require, you know, energy from outside world. It makes its own in the process.

And it produces two things. It produces biochar and a bio oil product. The bio oil can be used directly to make asphalt, pave a road.

And you get a carbon credit because that asphalt is a western carbon, right?

Or you can take that bio oil and it’s complicated. It’s not as simple as I’m going to make it that sound. They’re multiple steps in here.

And it essentially generates things like jet fuel for aircraft or marine fuel for big ocean going ships.

And this means that you can address some of those very difficult to decarbonize sectors of the economy.

So, you know, we can all drive electric cars. I would love to have a test, right? Probably my next car is definitely going to be a electric car.

Okay. Not necessarily a Tesla.

I’m not going there.

Anyhow, but we’re not going to fly in an electric jet. It won’t happen, folks.

And we’re not going to be sending huge container ships over to China with grain or bringing vehicles back from Japan or tennis shoes or whatever products are coming from around the world.

On these huge containers. We’re not going to run those on batteries either.

It’s just not going to happen.

And even, you know, heavy trucks been over the road semis combines in agricultural fields, earth moving equipment.

Some of this equipment is really difficult to electrify.

It’s going to take, you know, order of magnitude improvement in energy density, storage of batteries before we’re going to be able to electrify a combine in a field, a tractor, that kind of heavy equipment.

It works great for a passenger car, but it’s much more challenging for some of these other transportation sectors.

And the fuel that they burn is diesel or marine fuel or a jet fuel, not gasoline.

And as we look to decarbonize that part of our economy, we’ve got to find carbon neutral and ideally carbon negative sources of liquid fuels to do that.

And I know there’s been a lot of talk about using, for example, hydrogen run a jet aircraft.

And there’s some demonstration scales out there.

But think of the cost of completely rebuilding our jet fleet around the world.

And not only that, but of building the infrastructure to produce the hydrogen, store it and load it onto these aircraft.

You can’t afford that.

You know, not at least in the foreseeable future.

We’ve got to have drop in liquid fuels for these hard to replace hard to electrify transportation sectors.

And this pile oil that we can get from auto thermal fast paralysis gets us there.

It provides that fuel source and it provides the economic value to pay for the process.

So that the biochar can literally potentially even be given away to the farmers.

It’s amazing.

It’s so exciting to think about.

And by the way, I want to share with our audience that David, you provided us several links and images that will be including in the show notes on the auto thermal fast paralysis technology.

A number of videos, including at least one in which you are filmed talking about biochar.

And we’ve even got a scanning micron electrograph image of the biochar down it around the 10 micron level that will include in the publication.

And I want to remind our audience this is the why on earth community podcast.

I’m your host, Aaron William Perry.

Today we’re visiting with soil scientists and professor emeritus David Lair talking about biochar as one of the win-win-win opportunities we have to help tackle and address some of the systemic challenges that we’re facing right now.

I want to give a quick shout out to our why on earth community ambassadors and those who have joined our monthly giving program to help support our podcast series and our other stewardship and sustainability work.

If you haven’t yet joined the monthly giving program and you would like to, you can go to why on earth.org and click on the donate button and set any monthly level you’d like to give.

If you give at the $33 or greater level, we’re happy to send you monthly shipments of our regeneratively grown aroma therapy hemp infused soaking salts from way late waters and there’s $33.55 and $77 a month to get one three or five jars per month of the soaking salts as a thank you gift.

I want to also give a big shout out to our friends at Purium, the organic superfoods company that keeps me fueled and actually has helped me lose some weight and we have a special partnership with Purium where you’ll get $50 at least off your first order or 25% whichever is greater.

And it’s a 60 day money back guarantee no questions asked. Additionally, 20% of your purchases, all of your purchases come back to support the why on earth community and these are amazing delicious superfoods.

I’d like to call it liquid sunshine liquid Veritas and speaking of Veritas, the green healing energy and plants, the term coined by Hildegard from being in about 900 years ago, want to be sure to mention my new novel Veritas, the great healing is within our power.

This is available in print and ebook at Veritas book dot com. That’s V-I-R-I-D-I-T-A-S book dot com. And in this story, you’re going to follow the characters along as they visit many regenerative farms and as the main character Brigitte Sophia, brilliant computer scientist, goes through an extraordinary transformation and awakening of awareness as she experiences so many new aspects of

what it means to be alive on the planet right now and what is possible in terms of healing regenerating and restoring our ecosystems our communities even the health of our own bodies.

And I thought, David, it’d be fun to show here for folks watching the video. I’ve got a handful of the biochar here. This came from Rowdy Yates, my buddy up in Laramie Wyoming, his high planes biochar company and that’s another podcast episode. If folks are interested, we’ve got some video of his small scale technology there, farm scale community scale.

And it’s so fun to play with and we’ve enjoyed putting this into the soils here at Elk Run Farm where we’re located. And of course, one of mentioned, we’ve got our soil stewardship handbook available at yuners.org. This is the quick and dirty kind of get going to understand soil and its connection with climate health nutrition and even our own neuro biochemical health and well being at the individual level when we get our hands in the soil.

So there’s so much beautiful science on that now as well. And David, it’s so wonderful talking with you about all of this. I’ve got pages of notes here that I’m looking forward to consolidating into the show notes when we publish this episode.

And more than anything, I’m so excited about the hopefulness of the win-win-win opportunities that we have here at scale. And I know that big policy is part of what’s needed to move all of this forward.

And I also know that you’ve been a part of a really important legislative effort here in the United States. And I wanted to be sure to ask you about this Biochar Research Network Act of 2022 and how you’re anticipating not is going to potentially play out in the upcoming Farm Bill and what folks can do here in the United States were talking in terms of civic engagement to help support this bipartisan effort that

that you’re a part of, David. Thanks, Sarah. I really appreciate it. Yeah, well, I retired from Iowa State University. So I’m now a free agent, right? I can do what I want to. And I thought it would be a value to work with a group of colleagues and try to advance at the piece of legislation, basically, that will support

a research network, 20 sites around the US doing long-term biochar research to answer some of those questions that I was talking about earlier.

How do we get, how do we assure the farmer that we’re going to get a positive outcome and not a negative outcome on his farm or her farm with her biochar, with management system, with climate, with soil, and all of that being integrated.

We need that information going forward. And it’s going to be part of the economic package that accelerates the adoption of biochar systems in the US.

Certainly the bioenergy that I was talking about is the economic opportunity, but if farmers sees it hurting her yields, right?

That thing don’t want it. Okay. So we’ve got to have that research. And so we put together a team really of eminent scientists, my colleague and good friend Jim M.

and that who’s how to Washington State University and Batel Civic Northwest Labs.

I’m Berk Oblanko, University of Nebraska.

Chuck Hasselbrook, who is a politician. He’s actually a guy organized us at Chuck.

He ran for governor, State of Nebraska, also Senate, lost both of them, but he’s, you know, he’s, he’s deeply ingrained in the politics. He guided us through this. So I’m great kudos to Chuck.

And Johanna Salaman, who is certainly most probably most widely recognized biochar expert world.

Riton Lau, Riton Lau at the Ohio State University World Food Prize, Laureate.

Very widely recognized, Debbie Dunrose, Page Dunrose, who’s with US Forest Service.

We got together as a team and we wrote a referee publication called the integrated biochar research roadmap.

And this was published in 2021. And this was an academic effort and we tried to envision what research would be needed in order to take biochar to the next level.

To address some of the both the more theoretical to develop computer models and then to develop the very applied on farm research that will help land managers and farmers to, you know, really utilize this stuff appropriately.

And then Chuck helped lead us to contact people within the Department of Energy, within the USDA. We even spoke twice with people on the White House.

So, you know, we’ve had all these contacts and all this information and with senators and their aid.

And we managed to assemble a broad bipartisan. This is not a democratic initiative. This is not a Republican mission. We’ve got both parties on board.

And we’ve got this bill introduced in both the US House and in the United States Senate.

But it’s a standalone piece of legislation and the way Congress works, it’s never going to be, they’re never going to get around to voting on one little piece of legislation.

And what it would do is fund this biochar research network and get the research done that needs to be done.

This is known and in the House of Representatives, it’s HR 8596. And in the US Senate, it was S4895. And you’ll post that on your notes.

We sure will. Yeah. And you’ve got a link to the text of the bill. You’ve provided will include that as well.

Great. Great.

We can check that out.

So, how’s this going to become? How are we going to get this funding that we need for this?

The strategy is to get it incorporated into the 2023 Farm Bill.

That’s the way, you know, what do they say about? If you like sausages and you like laws, you don’t want to know how either of them are made, right?

I didn’t say that. Yes, I did. That’s life. But we still, you know, one could get cynical. I’m not going to get cynical.

It’s still positive and we’re going to move forward. And that’s what we are trying to do.

So if we can get this piece of legislation woven into the Farm Bill, we can get it funded and we can make this big step, really critical step towards getting biochar and bioenergy integrated biochar energy systems to scale up towards that gigaton level.

Well, so what you as a listener can do is to contact your senators, your representatives, and encourage them to support the inclusion of this bill in the 2023 Farm Bill.

Particularly if you’ve got your senator or congressperson is on one of the ag committees, either in the center of the house, because this is where they will meet the conference and throw things out and, you know, you know how it goes, right?

But that’s where the action will be and that’s where the final decision will be to fund this and throw this away.

And we want to have enough public support, enough people calling their senators and their representatives to encourage them to support this and build that public momentum.

We can get this thing funded and get the research done. We can build biochar towards that gigaton scale.

Now, I don’t want to oversell biochar. I’ve been involved this for a long time and I spent much of my research career.

I was at university working on biochar and agronomic and environmental systems and, you know, I want to know it.

But the challenge of climate change is so enormous that biochar by itself is not the solution.

It is a piece of the solution. We’ve got a layer on energy efficiency. We’ve got to, you know, develop whole new ways of generating, you know, solar, wind, storage.

We’ve got to put, you know, reforestation. We’ve got to do all of the above if we’re going to actually solve this problem.

But biochar is a significant piece and it can be scaled up.

My estimate is that here in the United States, between either offsetting petroleum with the bio oil and or the carbon we put in the ground from the biochar that is sequestered for a thousand years between those two.

We can have a net carbon reduction of probably close to a gigaton in the United States.

And then if you start extrapolating that globally, it’s probably almost 10 times that globally.

So is that is that an annual rate? Yeah. That’s amazing. That is amazing. That is the upper limit, right?

We will probably get there, but at least, and what is the upper limit limited by? It’s limited by the amount of biomass that can be sustainably put through this process.

Yep. That’s so exciting.

If you put the char back on the soil, you can just brand the biomass and burn it. It’s not sustainable.

Well, this is so wonderful, David. And I know that we’re going to have a few extra minutes together in our behind the scenes recording, which is made available to our ambassadors.

You do need the ambassador password to access that additional material along with some of the other resources we make available there.

If you’re not an ambassador and you’d like to become one, go to whyoners.org and you’ll see a lot of information and some pages about our current ambassadors and how to get involved in our ambassador network.

But before we transition to our behind the scenes piece, David, and have a continued chat on all of this, I want to just thank you for taking the time to visit with me and to share this really important information with our audience.

Before closing the podcast episode, I want to give the floor back to you to share anything additional you’d like to say to our audience, any closing remarks or statements.

Now it was a great time and thanks again for being on the show.

Well, Aaron, thank you for inviting me and giving me the opportunity to meet with you and with your audience and with the team you built.

You know, I guess we’re in very challenging times.

I mean, oh my gosh, politically, economically, the war in Ukraine on and on.

It’s easy to lose hope. It’s easy to.

We can’t.

We’ve got to be positive. We’ve got to look for solutions.

And you’ve got to do what you can do out there, right?

Take the action that is within your grasp and make the most of it, whether it’s on a personal level in your own life or in the politics, talking to your congressman, talking to your senators, whether it’s running for public office.

I encourage everyone to do what you can, what is within your purview to do and help us to solve these problems and help us to, you know, find ways to bridge the political divide that’s in this country.

That’s that’s probably the worst of it right now, other than the threat of nuclear war, but who knows.

So don’t lose hope.

Get involved and do good works. Thank you.

Well, thank you, David, and you’re clearly doing great work and appreciate you being on the show. Thanks again.

Thank you.

The YonEarth community stewardship and sustainability podcast series is hosted by Aaron William Perry, offer, thought leader and executive consultant.

Podcast and video recordings are made possible by the generous support of people like you.

To sign up as a daily, weekly or monthly supporter, please visit YonEarth.org-support.

Support packages start at just one dollar per month.

The podcast series is also sponsored by several corporate and organization sponsors.

You can get discounts on their products and services using the code YonEarth, all one word with a Y.

These sponsors are listed on the YonEarth.org-support-page.

If you found this particular podcast episode especially insightful, informative or inspiring, please pass it on and share it with a friend whom you think will also enjoy it.

Thank you for tuning in.

Thank you for your support and thank you for being a part of the YonEarth community.

0 comments