[Got Ingénieurs Sans Frontières?] Dr. Bernard Amadei, PhD. is professor of engineering and Founder of Engineers Without Borders, which works in communities throughout the world to design and install appropriate, sustainable technologies and infrastructure systems. Engineers Without Borders is working in 39 countries, managing over 500 projects, and deploying 17,000 volunteer engineers and engineering students world-wide.

In this special podcast episode, Professor Amadei, who is on the Y on Earth Community’s Global Advisory Board, discusses not only the sustainable systems, technologies, and strategies one might expect to hear about from an engineer and professor, but also the root causes of our complex and interconnected global challenges, and the ways in which we might approach their solutions – his perspective may surprise you!

Background

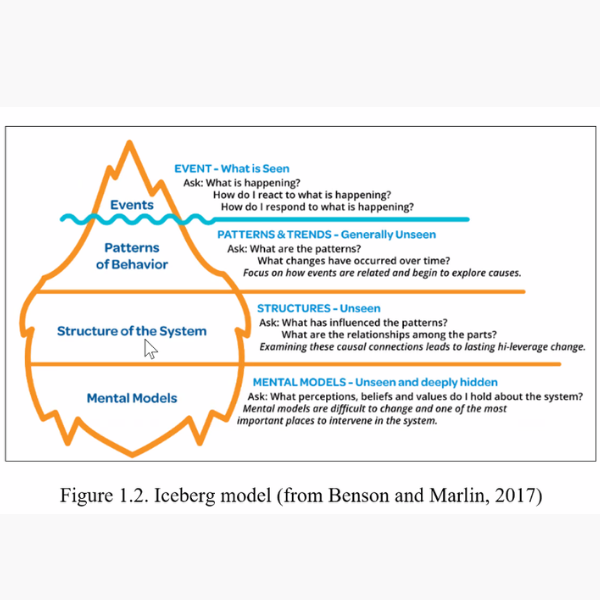

Recognizing that the very concept of the “university” was envisioned and established 1,000 years ago by mystics, Professor Amadei suggests that reconnecting with our spiritual natures by cultivating a sense of awe and wonder toward the profoundly complex and beautiful reality that we share on planet Earth. Suggesting that we could be do far better with our modern educational systems, he asks us to consider a future in which a “peace industrial complex” emerges and supersedes the “military industrial complex” about which President Eisenhower warned us almost a century ago. Professor Amadei encourages us to understand global peace, stewardship, and sustainability as not so much a set of technical problems to solve, but a matter of the “inner work” of cultivating ourselves as human beings, and transforming the deep-seated social constructs influencing our technology, economics, and governance systems, perhaps best understood through the “Ice-Berg Model” developed by Benson and Marlin (see image below). Quoting the medieval mystic Meister Eckhart, Professor Amadei emphasizes the importance of being in service, and reminds us that “The outer work cannot be great if the inner work is small.”

ABOUT DR. BERNARD AMADEI, PHD

Dr. Bernard Amadei is a Distinguished Professor and Professor of Civil Engineering at the University of Colorado at Boulder. He received his Ph.D. in 1982 from the University of California at Berkeley. He is the Founding Director of the Mortenson Center in Engineering for Developing Communities. He is also the Founding President of Engineers Without Borders – USA and the co-founder of the Engineers Without Borders-International network. He is the author of numerous peer-reviewed scholarly articles and books, including Engineering for Sustainable Human Development: A Guide to Successful Small-Scale Community Projects and A Systems Approach to Community Development Projects. He is currently writing another book about climate security, peace, and sustainability. Among other distinctions, Dr. Amadei is an elected member of the US National Academy of Engineering and the National Academy of Construction. He is also an elected Senior Ashoka Fellow. Dr. Amadei holds seven honorary doctoral degrees (UMass Lowell; Carroll College; Clarkson; Drexel; Worcester Polytechnic Institute; the Technion in Israel; and SUNY-ESF). In 2013 and 2014, Dr. Amadei served as a Science Envoy to Pakistan and Nepal for the US Department of State. And, Dr. Amadei holds a commercial pilot license (multi-engine land, instrument).

RESOURCES & RELATED EPISODES

Episode 94 – Tom Chi, Founder, At One Ventures

Episode 51 – Jonathan Granoff, President, Global Security Institute

Episode 25 – Hunter Lovins, Author, “A Finer Future”

IMAGES

Transcript

(Automatically generated transcript for search engine optimization and reference purposes – grammatical and spelling errors may exist.)

Welcome to the YonEarth Community Podcast. I’m your host, Aaron William Perry, and today

we’re visiting with the founder of Engineers Without Borders, Bernard Amadei, Hey Bernard.

Hey, how are you Aaron? I’m doing great and really looking forward to our conversation today.

Me too, I think it’s going to be interesting.

Yeah, I do too.

Dr. Bernard Amadei is a distinguished professor and professor of civil engineering at the University of Colorado at Boulder.

He received his PhD in 1982 from the University of California at Berkeley.

Dr. Amadei is the founding director of the Mortensen Center and Engineering for developing communities.

He is also the founding president of Engineers Without Borders USA and the co-founder of the Engineers Without Borders International Network.

Among other distinctions and the list is long, I’ve got several pages here.

You don’t have to go straight ahead.

Dr. Amadei is an elected member of the U.S. National Academy of Engineering and the National Academy of Construction.

He’s also an elected senior Ashoka fellow.

Dr. Amadei holds seven honorary doctoral degrees from UMass Lowell, Carroll College,

Clarkson Drexel, Worshester Polytechnic Institute, the Technion in Israel, and SUNY ESF.

In 2013 and 2014, Dr. Amadei served as a science envoy to Pakistan and Nepal for the United States Department of State.

And he also holds a commercial pilot license.

Maybe we’ll talk about that too at some point.

But what has struck me in learning a bit more about you and your background from a professional and academic standpoint,

and having been aware of your work with Engineers Without Borders for many years now,

is that we’re not only going to be talking about technical and linear, so to speak, items today.

We’re going to actually be talking a lot about holistic, interconnected, and even one might say spiritual topics.

Okay. I mean, Aaron, good point.

You know, I tell everyone, if all the problems in the world were technical, we would have solved them by now.

I think we know how to do it from a technical point of view. I think what we are lacking is whether the more inner dimension of human beings had,

we essentially addressed the global issues that we are facing today.

Not with new tech, new AI, new whatever you are saying that it has to do with the inner work of our institutions,

the inner work of decision makers.

There’s a great quote from a mystic of my study of the 13th century, I guess,

who I’m going to paraphrase, we’ll say that essentially the outer work cannot be great if the inner work is small.

And so the question is, what’s the inner work of our institutions today, looking at what they do from an external point of view?

And I can really question about the lack of inner work, right?

So for us engineers and scientists, usually it’s coming up with some new theories, new technology.

That’s what we need on our planet today. How do we create more of an inner work that translates into a better planet?

And obviously right now so many people are focused on the development of technology, whether it’s in the digital realm or other types of applied or appropriate energy technologies or whatever else is being deployed around the world right now.

And I’m just wondering, it doesn’t seem from my perspective that the inner work is a part of that milieu for most folks engaged in that kind of work.

And I’m wondering Bernard, from your perspective, how might we look to bring that inner work more into the mainstream and more into the four of the consciousness of folks in a very technical society?

That’s a good remark and a really good question. I don’t really have an answer to that question.

Look at the educational system that we are all exposed to starting the age of six or way to 18.

We don’t talk about inner work at all. We don’t talk, I mean, it’s not part of the discussion.

It’s about doing this, doing that, getting a good job, making good money, or what have you to help in the economy, or what have you, but what about the inner dimension of the decision makers?

And where do you learn that? That’s in that, like we did, wisdom schools or where wisdom is part of, of part of the education.

You know, somewhere as you, it’s easier to speak a foreign language when you learn it early on in life.

Well, what about, you know, teaching young kids about wisdom, about the inner dimension?

Not talking about religion here, we’re talking about, we’re discovering what we are as human beings, introducing sustainability as early as possible, introducing healthy mind, healthy body, as early as possible.

It should be part of, my opinion should be part of the education. And it’s likely that, like a foreign language, research in the kids, we will remember that as we move in two teenage years and adulthood.

Of course, we make mistakes, that’s not part of the equation, but being able to get back in-house.

And an analogy that crosses my mind is that I read somewhere that in the old days, people in Midwest, we’d go out doing the tornado season, or tornado season.

The farmers would attach themselves with a rope to the house, so in case they were stuck out there, they could go back home.

So I like that metaphor because what is that rope that we have when we deal with, especially with steel with complex issues in life? You know, we all deal with that.

What is that rope that brings us back home?

Because home is where we want to be, we want to be in a safe place, and whatever that safe place is, is certainly different for you and me.

What is it that we have that brings us back home? Well, what is that life-streamed life, because it’s a life-saving rope, that brings you back home when you pitch the fan.

You know, you had made all of it, you cannot control it, and the fan is spinning faster and faster. How do you go back home?

Yeah, it seems to me that, and this is obviously a big part of the work that we’re doing at the Y-Earth community, that community building, and having those connections, those human connections, while we’re also cultivating our own inner lives, inner dimensions, is necessary.

Maybe there are some other things as well, but it seems like those two community and the cultivation of the inner experience is critical.

You know, the term community comes from the Latin, I read about it, and says it’s about the gift of being together.

So you can be together with a group of people, if it’s not a gift, don’t stay there, it’s not a community, right?

Yeah. And we were talking about education in general. You know, universities were created a thousand years ago, they were tech, for young people to find a place in a universe.

Yeah. Is that the mission of our universities today? It is not. Right.

Right, finding your place in a universe, mostly at the time, young men, but today, where do you find your place in a universe today?

You probably don’t, you know, have been at the university for 40 years teaching, I’m almost done here at the end of this semester.

I don’t think that the mission of the University of Colorado is to find, for young people to find a place in a universe, not just the University of Colorado, of course, but as a university.

So what’s that mission? I mean, it’s, to me, the university should be a place where you discover yourself. You know, we talked about it before, but this idea of, I asked my students usually that question, what’s your mission statement?

What’s the gift that you and he can give to the rest of the world? And are you a loose cannonball in the ocean of life moving around, left or right there?

What you have, you know, your gift, of course, that the answer is, what is your gift, may change over time as you grow up and discover essentially who you are.

But to me, it’s an important question. What’s your mission statement?

I reflected a lot on that. Initially, my mission statement was long, you know, and just summarize it with one word, three words, I mean, to be of service forward, to be of service.

That’s it. So, you know, so I think finding your mission statement, your gift is should be an outcome of any form of education.

That’s so beautiful. So at the end of high school, we asked you that last homework assignment.

Okay, start another again, at the end of four years of college. Okay, what do you think? Are you better off today? Do you know who you are?

And the answer may be no, which is perfectly fine too. It takes a lifetime of some people, many lifetimes to find out who they are.

But, must your mission statement, what’s your gift that you and he can give to the rest of the planet?

Yeah, so important and really beautiful to engage in that inquiry. And I’m curious, you know, we were talking recently about the fact that the university as originally conceived many, many centuries ago was conceived by mystics.

You sort of just alluded to this a few minutes ago. And I’m curious, in your opinion, what was it that was going on in the 11th, the 12th, the 13th centuries?

In Europe as that connection with the Middle East had come alive again. And there were, there was something so special in those times that it seems got really quite confused and jumbled in the ensuing centuries.

Share with us a little, because I know this has not even been explored.

I’m actually interested about the mystics of 11, 12, 13th century there. And it’s my mentor, Matthew Fox, who has written 40 books essentially on the mystics and my life changed completely when I met him in the late 1990s.

And I’m really discovering a bunch of individuals, men and women, that in my story cards, and Francis of SCC, the God of Bingen, Julien of Norwich and all those individual, all those eclectic people, Thomas Aquinas and all that one.

We’re just rediscovering this concept of awe, you know.

And to me, the wow, I mean, I got it, the wow factor. It was at that time, and Matthew Fox has a beautiful book and it’s an original blessing. It’s the original thing.

Wow, wow, of course, you don’t think too many people to church on Sunday was with that marketing tagline, but how is your own blessing?

It’s such a positive way of looking at how we stand as human beings in the universe, right? And that lasted about two, 200 years and then actually the plague came right stop the whole thing, pretty much.

This concept of which you know, blazing and after that was, you know, as you know, today seeing and guilt and all that nonsense that you see that you see in the world.

But we’re discovering this concept of the wow factor, right? To me, good engineering is an engineering where you can look at it and say, wow, if you look at any practices,

if the practice you do, not just engineering, doesn’t give you a sense of wow, of awe and wonder.

And the thing that what the mystics essentially helped us to rediscover is this concept of awe and wonder.

Being an awe and wondering about creation, right? I mean, creation, not just, you know, in seven days. I always laugh about the seven days of creation.

You know, I’ve been focusing over the past 20 years on system thinking and so on.

Okay, you hear from Denise is on the first day, God did that. A second day, God did that. Third day boy, I mean, based on the Bible, God is a linear thinker.

Really, when you look at a sign that science of the past 20 years or 50 years, it’s discovering that the universe is not a great machine.

It’s a great thought that the universe is beautiful, that its systems are everywhere.

So I have a disconnect between how God is described as a linear thinker in the Bible in Genesis.

And at the same time, see, I’ve got created everything, which is a system of systems and so on.

So it’s just a disconnect there between the two, but it is the way it is.

But this idea of, yeah, I mean, the mystics really changed my life. I mean, I’m so grateful to Matthew Fox and the few others for bringing such a Christian mystics.

But then you also have the Muslim, Sufi mystics also who essentially this idea of who is discovering love.

The beloved and the divine has a lover, right? I mean, where you have an intimate relationship with the divine.

And wow, you know, again, wow, you can say why again, because it sounds beautiful.

You know, if the mystical tradition that you follow or spiritual tradition does not bring you in awe and wander with creation and the universe,

then you may want to decide to switch to a different tradition.

The idea of sin and guilt and so on, even sin, I mean, concept of sin and mistranslation, I mean, sin comes from the Greek.

It means to me to miss the mark. You know, I mean, words that have been used like redemption, I mean, repentery.

I mean, in RMA, it’s metanoia. Change your mind.

John the Baptist was asking us to change our mind, not to repent and feel guilty and sinful and all that stuff.

So, I mean, we’re discovering that stuff that, wow, again, it’s a wow factor that to me is so critical.

And so the question of fine, you discovered that a wow factor, how do you bring into practice?

How do you live with that wow factor on a daily basis? With your family, your friends, your work?

How do you bring into practice, the action path? So contemplation on one side? Yeah, wow.

Action on the other side. So how does contemplation translate into action?

Beautiful. These are such beautiful inquiries.

I have to admit that in my book YonEarth, there’s a chapter called Wonder that is all about this experience of awe and cultivating this experience of awe.

And deepening in our awareness, our understanding of just how important this experience is to our humanity, to our humaneness.

And I’m really curious, your thoughts on how we bring more of that into the mainstream.

Maybe it’s I’m reiterating my earlier question in a sense, but I wonder about this quite a bit.

How do we reintroduce, especially in the secular academic context where sort of all things, a spiritual and I give talks all around the country and internationally sometimes in secular academic settings and sometimes in faith communities.

And it’s interesting the language, the code switching the different rules so to speak of what’s permissible and what’s not in these different communities.

And I really I really wonder how do we do more of this in the mainstream academic world?

Oh, that’s a good question. I’ve been wondering about that for the past 40 years.

And in fact, my next book is the title is called Engineering with Soul, S-O-U-L.

I love Soul, these are four letter words that you never hear on campus.

We hear also four letter words, but not those.

So, in fact, I remember painting the concept of love into a class on sustainability and the idea of the semester.

In fact, cosmology, I remember saying, okay, I was teaching sustainability two inch in years.

And the first two or three weeks was the cosmology.

We discovered this concept of love and wonder and I used the book of Thomas Barry and Brian Swim, the universe story.

And I asked the students to read the universe story as they were reading fiction.

Because it’s a great story.

You know, and had we were talking about the war factor, the war of essentially the universe story.

Whoa, whoa, whoa, 13.8 billion years essentially.

Whoa, everything, it’s something.

I’m thankful for, it took 13.8 billion years last night, yesterday at Rice.

And I was looking at those grains of rice.

It took 13.8 billion years for the grain of rice to be in my mouth.

It’s not chubby, not bad.

You know, I mean, so again, I think we can we discover this concept of war in a grain of rice, in a flower, in your partner, in the visage of your partner, in your children, in your family, everywhere.

And it’s everywhere.

So, to me, I really believed that miracles are not an exception. They are the rules.

In fact, what we call miracles, because, oh my God, something is happening, good, because we were not expecting it.

Well, it’s something about us, right? When you turn the whole thing around and say, well, you’re a miracle.

How many miracles? My son is a miracle. My daughter is a miracle. The cat is a miracle. Everything is a miracle.

But again, we discover in the war.

You know, I mean, the trillions of cells are right now in your body. Essentially, you know, each one doing what?

10,000 chemical interactions with you.

Every second, right?

How can you not say, well, in some things like that.

So, it’s really discovering this concept of war and wonder in everything we do.

I love it. It reminds me of, I think, it wasn’t Einstein who said that you either experience life as if nothing was a miracle or as if everything was a miracle.

How would you agree with him? That everything is a miracle.

In fact, it’s the rule wasn’t in the exception.

And then your question is, where do you learn that stuff? I mean, not at the university, I can tell you that.

In fact, the university is going to do the opposite. It’s going to, and that’s based on what the cat and Newton told us about 300 years ago,

essentially matters of the mind and matters of the soul, essentially completely separate.

That’s bullshit, excuse me, the term.

That’s in me how we’re discovering that the two are interacting.

And so, I mean, academia is very, to me, I’m glad I’m finishing my 40 years of academic career because I cannot take it anymore.

I mean, in fact, I always joke that we should have, I should create a academic anonymous way.

You know, I can, what are the 12, what’s the 12th program?

So that we can remove the academic nonsense out of academic division, right?

Academic anonymous. That would be an interesting program.

But, you know, there’s no soul. There’s no soul on campus. That’s the way I look at it.

You walk around. I mean, God, this is so many. These are able people.

And when the academic world is, don’t get me there because I’m coming out of it with a lot of bitterness, right?

But at the same time, I need to change my mind, right? I can look at it. That’s okay.

40 years of experience, I’ve learned some stuff.

So, what am I going to do when I grow up now?

Yeah, well, let me all come to that question, what’s next?

But before going there, I want to acknowledge that notwithstanding some of the critique you’re offering right now of the academic world,

you’ve also had such a tremendous influence in it. And especially on the discipline of engineering around the country and worldwide.

And when you created engineers without borders, what about 20 years ago?

I gave it that kick.

I’d love to hear what caused you to create that in the first place.

And also, please tell us about now how many thousands of folks are involved here in the United States and many more thousands worldwide.

Can you give us an idea of what the organization looks like today, but first tell us about how it got started?

I got started. It was really here, actually, in this house. And in 1997, we needed some landscaping down in the backyard.

And I picked up a landscaping company from Laumont, out of the phone book, The Yellow Pages.

You have to be careful about what?

What are Yellow Pages?

You don’t remember the Yellow Pages. Well, they were Yellow Pages at one time in the history of mankind. And so I selected a company at random.

You have to be careful about random processes because they can change your life.

And three people came a few days later. They were all from Belize. And all three of them were working in that company in Laumont.

And they told me about the needs of my engines. And they told me, one of them will come over and help us.

So two years went by, in 1999, 1999, when I got an email from one of them and said, hey, we were in your backyard a couple of years ago.

You mentioned you could help us in developing a curriculum for young Mayan kids in technology and STEM.

And so as I guess, I went over there and visited a bunch of Mayan villages, including the village of San Pablo.

And came across the village, really poor.

And it really struck me. This idea of being of assistance to others was not new to me. I had done volunteer work at the border shelter for the homeless.

So being of service to others has always been part of my DNA.

But I think that trip to Belize was kind of a convergence of two things, being of service on one side and engineering on the other side.

So it was a very singular point in my life, but that way.

So I mentioned that to the students at CU, I was teaching a class on engineering geology. And the students said, well, we want to be part of it.

We want to be part of it. So 10, 15 students signed up. We had a technician who came also.

And we went over there, collecting data. And the students were super excited. Super excited about the project. It was a water project.

They held it two times, two times, actually, until the different solutions came up. But essentially, when I asked the students, well, you’re excited about it.

And they say, well, we want more meaningful engineering education. And that concept of meaningful is something that has, that really struck me.

I said, how come you take those classes? You know, they should be meaningful to you and say, no, no, no.

We tired of doing those problems at the end of chapter five. And as I’m tired of grading them anyway.

And then so that’s how that was the, essentially, the birth of engineers was about it. It was driven by the students.

The students wanted to do something different, learn engineering in a field, rather than in books.

And then so engineers without borders exploded. And it was not, you know, startups for the people who are watching this program and we have done startups.

You know, quite well. And you look quite well too. You’re wrong. It’s doing a startup is not easy.

Most people essentially, you know, what 10% of startups essentially make across the big valley of death there.

But we keep on going. You keep on going. And that’s the beauty of that America is that here you can keep failing. It’s okay.

In fact, I don’t talk about failing anymore. I talk about learning lessons. You don’t fail. You learn lessons. Oh, you succeed.

Absolutely. I’ve got a few of those on your mind.

You know, quite well. But it’s painful. It’s not easy. It’s not an easy journey.

But the students were always there to remind me of that the journey was worth continuing.

And so now we have about 17,000 members in the United States. I would say half and half.

Half students have professionals. The students become professionals and they stay in the organization.

The headquarters in Denver. I don’t run the organization anymore. I’m just one voice on the board.

But yeah, we have helped two and a half million, two million people in the world working in 48 different countries.

That was before COVID. We cut down after COVID, not trying to get back on the saddle.

But this idea of to be of service. And I look at it and I say, whoa, why is it that those students were so excited about being of service to others?

There was nothing for them to do. They wanted to be of service. Yeah, you could do.

You build a concrete canoe or you build something like that. But the idea of learning engineering by going to the field,

by talking to some real people, providing us actually clean water to people.

I mean, I mean, it’s amazing. We’re providing basic electricity to people.

You should see how people just provide one light bulb. Like right now in this room, we have 20 light bulb.

But just to have one light bulb. And I remember those faces in Afghanistan when in Kabul,

when they brought light to electricity to Kabul, where there was not a lot of electricity.

But the kids would go onto the street lights and do their homework assignments at night.

Whoa, desperate to learn something, right? I don’t see too many high school kids and students at CU doing homework assignments like that.

But there was something really special in baking. There’s something special in baking,

essentially water, in water, electricity, to food, to communities around the world.

And that’s when I want to do more when I grow up, when I’m going to retire on the end of this semester.

When I’m going to do women, I usually tell people, TBD, right? I’m determined.

But certainly to be of service, yeah?

Beautiful. But being of service to me is, if you remove that, then I die.

I mean, I really need to leave part of my DNA. You pay me to be of service.

You don’t pay me to be of service. Fine, too.

So the money is not key at all. Of course, it’s nice to get your airline ticket paid.

But just to be of service, in itself, it’s to bring your soul into, again, doing resolve.

To me, engineers, resolve borders is a good way of expressing that concept.

Where you bring the mind, body, soul into your work, into helping a human being,

who now has clean water, has little bit of hope.

Creating such these small businesses, I like to turn doing well by doing good, right?

Often you have people to do good people, to do well people.

I think the challenge is to be in the middle doing well by doing good.

Then it’s an interesting journey.

It’s not only a job, it’s Matthew, Fox, and Thomas Berry talk about the great work.

What’s your work? Not your job. What’s your work that keeps you going?

Right? Where you wake up in the morning and say, wow, what am I going to do? It’s my day.

Am I going to improve the world? Am I going to improve myself, my family, I’m sorry?

That’s work. Great work.

I did a beautiful book to read the great work.

On page 9 to 5 p.m. job, Dailin.

Two hours of driving in the morning, two hours of driving at night, something walking.

Some people have to do that, I guess.

But what’s your great work?

Yeah, so wonderful to reflect on that, another inquiry.

I want to ask just to round out my ability to write a synopsis of our discussion together.

You mentioned 17,000 members in the United States.

Do you know how many are involved in the global network of engineers?

Of course.

There’s no, but 80 different engineers with our voters groups on the world.

I did not create all of them. I’ve helped create actually some of them.

But the idea is to create a network of young people, and also senior people.

Professional people can be of service to humanity in different countries around the world.

There are about 80 groups. If you look at engineers with our voters international,

you have a list and they have all the different groups.

Some of them are students and some of them are professionals.

Some of them, like in our case, we are both.

We can do students and professionals.

The professional chapters tend to take bigger projects.

It could be a bridge construction, for instance, over a dam or something.

Student chapters that could be a rainwater catchment system, medical ecosystem,

sanitation system, something usually smarter.

Yeah, that’s interesting and that’s helpful.

While we’re talking about some of those technological solutions and infrastructure,

let me ask you this, notwithstanding some of the concerns and critiques we might have

and share regarding some of the technologies being developed right now.

Is there a technology or a family of technologies that are making significant advances right now

that most excite you in terms of the well-being of humanity worldwide?

I don’t think it’s the technology itself. It’s what you do with it.

I’ve been really interested in over the past few years in the field of

our relationship between engineering and peace.

There’s a group in Washington, D.C., called Pistach Lab,

that was created by a good friend of mine, Sheldon Himmelfrop.

You can go pistachlab.org, and you’ll see that there’s a lot of technology

in bringing peace into the world, right?

Technology can do, it’s not the technology itself.

We can divide people. We can bring people together.

Pistach Lab is to look at using technology for the betterment of mankind.

A vision we have, and then a vision that I talk about a lot,

is this concept of peace-industrial complex.

Can we create a peace-industrial complex in the world that essentially competes

with the war-industrial complex that was created pretty much a hundred years ago?

Imagine, I would imagine people who contribute to the war-industrial complex.

I don’t think that those people are mean.

They don’t wake up in the morning, so I’m going to kill people.

But they make money.

So imagine, can we create a peace-industrial complex where people make more money

in contributing to peace than in contributing to war?

And the answer is, there’s no winner.

You have eight billion customers here with you.

Eight billion customers, when they clean more, they need food,

they need transportation, they need communication,

they need health access to health, and what have you there?

If you look at what the filtration system showed me,

what the filtration system today that is affordable, reliable,

that doesn’t bite down essentially after two days or one week or so.

And that can be essentially scaled at the global level.

We don’t have that.

And you find systems that are about 20 bucks, 50 bucks.

Well, you can go to New York, and I can go to ARIA and buy a system there

that gives us clean water whatsoever.

It’s not sustainable.

There’s no way a small community of people who make a dollar a day

can afford such a system.

How come we don’t have, if how come people don’t make money

in creating a water filtration system that are good for eight billion people?

Same thing about electricity, something about food distribution.

We have plenty of food on our planet.

We have plenty of water on our planet.

I think the problem is water management.

Food management, that is not good.

Energy management, that is not good.

It’s not management, but that’s not something to do with the resources themselves.

Yeah, absolutely.

The side note on this and data point that I find to be really impactful

that of the food we grow each year, we waste a third.

And the carbon emissions from that food decomposing,

often in landfill situations, is enough that if it were a nation state,

it would be the third most emitting country in the world,

greenhouse gas emissions, just following China and the United States.

So we have plenty of food.

We have 50% more food than people are eating courage.

We mentioned one third, but I read 40%.

Yeah, maybe it’s up to the world.

And there was a sign that see you more than that.

40% of the food that we get is wasted.

Water, something, how much water is wasted because pipes are not leaking everywhere.

That makes absolutely no sense.

You mentioned greenhouse gas emissions because of that wasted food.

Yeah, it makes absolutely no sense.

But it has to do with the management of the resources,

not the resources themselves.

The technology, I mean, I can bring a nice pen.

That pen can hurt somebody.

You can write a beautiful poem about it.

It has nothing to do with the pen in itself.

I think that we are right now with the Fox at Peace Tech Lab,

my colleague Sheldon has developed an interesting collaboration

with Fox at Oxford, this side of misinformation.

In fact, they are planning to create a, you know,

you heard of the IPCC for climate change.

They are developing essentially with funding from several foundations.

The equivalent to IPCC and misinformation.

Right.

I mean, because misinformation, disinformation, bad faith information,

kills people.

Absolutely.

It’s actually very dangerous.

Again, that technology information in itself is fine,

if you use it wisely.

Right.

And so misinformation was looking at AI a few days ago,

chat GBT.

You know, you can have the ask the questions

and that the computer essentially answers essentially everything

you need to know.

The question is, is what you read is true or not?

I mean, someone could control that, the package of information

and misuse it completely.

Yeah.

And if you have tried chat GBT,

it’s with Eastern November of 2022.

Asked right the book, in fact, I just finished my book there,

what is the first draft of it.

And I bumped into chat GBT.

And I can ask, chat GBT,

write the book about, I don’t know,

the one I’m working on,

this climate security piece and sustainability.

It’s going to write something.

1.0, introduction, 2.0, and so on.

It writes, they will ask, you can do it,

a table of content.

You can ask, write the book on permaculture.

Yeah.

And not permaculture.

AI will write a book, it may not be true,

but it says, but just a matter of time,

when AI essentially is going to be more intelligent

than human beings.

For two reasons, number one, AI increases in capacity,

and human beings are essentially getting down there and down there.

So that singular point,

is going to happen sooner than later,

because of the domification of humans.

Imagine students not can go to AI and say,

okay, the paper that is good tomorrow,

write the paper on permaculture.

You tell it in, and they get a good grade.

Have they not anything known?

So the academic world would have to change.

What we are seeing today is going to make some big changes

in how we are educating young people

and how we make decisions in the world.

But again, going back to our discussion earlier,

how do you bring wisdom in there?

Well, speaking of AI,

I’ll take this opportunity to remind our audience,

this is the YonEarth Community Podcast.

I’m your host, Aaron William Perry,

and today we’re visiting with Bernard Amade,

the founder of Engineers Without Borders.

And of course, AI is a thread of theme that I deal with

in my new novel Veridi Toss,

which is a term coined by the Mystic Hildegard Fund,

being in that Bernard mentioned earlier.

And in the arc of the story,

there’s this emerging wisdom that takes us

from the AI of artificial intelligence

to the AI of authentic intelligence

that comes to us through the ages

from the esoteric traditions,

the traditions and teachings of various luminaries end of

indigenous cultures and wisdom.

Bernard has a copy here of Veridi Toss.

I’m reading it, by the way, Aaron.

And as I mentioned to you before,

I don’t want it to end.

Because I would be sad the day when I reached the last page,

which is a page, I don’t know, something.

Five something.

Five hundred something.

It’s a page turner.

Five hundred forty two.

It’s a page turner, but there’s so much information in there.

I do believe Aaron is a Renaissance man.

And they are very rare when you meet a Renaissance people,

men and women, of course.

On this planet, I can count about maybe a handful of people

like him who are exploring new ways of thinking.

And especially deeply rooted in wisdom,

wisdom tradition.

And that to me, wisdom tradition from the West

and wisdom tradition from indigenous cultures as well.

So if you have not, it sounds like a commercial,

but if you have not read this book,

you may want to read it because it’s a great page turner.

I read it before going to sleep.

It doesn’t put me to sleep.

But it’s a great way of relaxing and finishing the day.

That’s wonderful.

Yeah.

And if you would like to get a copy of the book,

we have them in print form as well as ebook digital form,

you can go to Veritasbook.com.

It’s v-i-r-i-d-i-t-a-s book.com.

And of course, I want to take the opportunity as we’re discussing.

We could say this episode is brought to you by Veritas today.

I want to be sure to thank our supporters,

our ambassadors, our monthly contributors.

We have many folks giving on a monthly basis to the Y on Earth community

to make this podcast series possible as well as the other outreach work,

gatherings, and resources that we provide to the communities around the world.

If you haven’t yet joined our giving program and you would like to,

you can go to yonearth.org and click on the donate button and set it up for any amount.

If you’d like to give it the $33 a month level or greater,

we will be happy to ship you a jar of the waylay waters biodynamically

and regeneratively grown hemp infused aroma therapy salts that are wonderful

as a thank you gift.

So check that out, set that up again.

Thanks to everybody for your support who are already part of the program.

And Bernard, I got to say that right now the Y on Earth community is working on our

five-year strategic vision.

And we see there are several things we can do in collaboration with many other organizations out there

to have even more positive impact in the world.

And yeah, with that as a mention, I want to ask,

you know, what are you for seeing as you kind of, quote unquote,

grow up here with your upcoming graduation.

I guess it’s a retirement from 40 years of being a professor.

And, you know, hopefully we can plant the seeds of us doing more collaboratively

coming back together.

But do I think that’s a lot of effort as you know.

And I think that what I’m looking for more is getting involved in some projects and learn.

Learn from, especially learn from the native traditions.

I mean that it should not be, it’s not sentimentalism.

Of course, native traditions had their own problems as well.

But what can we learn?

Why do we learn about sustainability today?

I mean, our two places in my opinion,

learning from the native traditions, and learning from nature,

and the old ways of biomilically being invited before.

What can we learn from nature?

That’s what the 4.6 billion years experiment in sustainability.

If it’s not sustainable by now, you know, then we might as well, you know, quit.

So what can we learn from nature?

And that we acquire humility, that we acquire wisdom, that we acquire saying,

I don’t understand, you know, teach me, tell me.

It requires sitting down and being silent and being quiet.

It’s also requires being able to listen, which, in my opinion,

is a big problem in our society today, to be able to listen and live in humility.

You know, it doesn’t mean living in a cave, but understanding that what, you know,

we can do well by doing good, we can, we all have,

we want to change the world, as Mark again, he talks about,

and he wants to change the world.

You need to be the change that you want to see in the world.

What is that?

And the thing that, and that, the answer to that question is,

it’s different for you and me, right?

But we won’t contribute into something good.

Right.

So you have 8 billion people on our planet,

but ultimately, it’s taking that homework assignment.

What is the gift that you only bring?

That you only bring to the world.

Yeah.

And sitting down, nothing that hurts you, all your people listening to this,

to go to a coffee place or a tea place, and say,

okay, what’s my mission statement?

You can change it as many times as you want,

but we all have a mission statement.

What’s your mission statement?

What is the gift that you only can give to the world?

And the best one time I was in Kathmandu,

and I was in front of a Buddhist monk, and I asked him,

what’s the meaning of life?

And he told me, chocolate.

Chocolate?

Then he immediately went to Siri and asked that question on the phone.

And sure enough, I did that one time after asking that question

ten times, I got chocolate too.

But what’s the meaning of life?

The answer to that is, you find your gift.

And what’s the purpose of life is to share that gift.

And not to mean that I’m very content with those definitions.

To find your gift and to share it with others.

Amen, and ahu to that.

Bernard, thank you so much.

We’re going to, of course, take a few minutes

to record our behind-the-scenes segment that is available to our ambassadors

and our Global Advisory Board.

So if you’re interested in becoming an ambassador, again,

you can go to yunner.org and engage with us there.

And so, yeah, before we sign off from our main podcast episode, Bernard,

and yeah, let’s write something together.

And when you’re…

Let’s do something together.

Absolutely.

My thing is easy.

Doing it’s more difficult.

Absolutely.

And when you’re forthcoming book,

Climate Security Peace and Sustainability comes out, you know,

it would be wonderful to podcast again on that.

But we’ve got a lot to do, Bernard,

and I’m looking forward to exploring ways we can collaborate in action and in writing.

And before we sign off, I just want to invite you.

If there’s anything else you’d like to add and share with our audience.

And thank you so much for taking time to visit with us.

You know, this is what I go back on to the back to Aaron’s book.

In there, you meet some very interesting people.

And if you ask Aaron,

if those people are real or not,

he will answer, yes, somehow real.

And I’m glad they are real, because I want to meet them.

And some, of course, it’s a fiction book.

I created, you know, in his brain.

But read that book.

And let us know what you think of it.

Plus, he gives you the latitude and longitude

of all the places he has visited.

So, nothing prevents you on weekends when you’re looking for something to do

to go to those sites and meet the interesting people he’s talking about.

That’s right.

I really like that.

It’s not just fiction, it’s practical fiction.

Yeah.

It’s a new genre.

Yeah, there are a lot of nuggets and treasures there for folks,

to discover.

So, thank you for writing that book.

Yeah, my pleasure Bernard.

Because someone has a lot of money,

he has to make a movie out of it.

Yeah.

I think a great movie can be made out of this book.

Maybe a three-part series,

or four-part series of very details.

I didn’t know that very details was from Hildegout of Bingen.

Yeah, it’s a term she created,

a Latin-inspired term that means the green-healing energy

of the divine that flows through plants.

Yeah, and that’s Pajeric, so that can be.

Yeah.

Yeah, and Hildegout of Bingen was passing up a group of vegans

in a woman who decided they could not join the church

because they could not be ordained.

But they created all the group of women.

I think you see them in Belgium,

you see them in Germany.

In Bruges, we created a group of women.

And there’s a heritage there way on the women,

decided to live a more ski-type of life,

it was humidity and so on.

But they were not ordained by the Catholic church.

So something to explore.

Yeah, it’s interesting.

I know she also corresponded and was friends

with Bernard de Clarevo,

who is one of the founders of Knights Templar.

So a very interesting history.

They’re very interesting person Hildegout of Bingen.

And this idea of finding energies

who plants and finding wisdom,

it kind of ties well with this idea of original blessing.

Yeah.

Positive.

Yeah.

It’s all, it’s beauty.

You know, it’s a rediscovering the sacred

through everything you touch,

see here, every day.

So beautiful.

And as I said,

in the Hopi Elder speaks,

everything we do now be done

in a manner of sacred ceremony.

Thank you so much, Bernard,

for this wonderful conversation

and for all that you’re doing

and have done for our world.

You do too.

And we only do all the pots now.

Yes.

Absolutely.

Bye-bye, everybody.

Bye.

The YonEarth Community Stewardship

and Sustainability Podcast Series

is hosted by Erin William Perry,

author, thought leader,

and executive consultant.

The podcast and video recordings

are made possible by the generous support

of people like you.

To sign up as a daily, weekly,

or monthly supporter,

please visit YonEarth.org-support.

Support packages start at just one dollar per month.

The podcast series is also sponsored

by several corporate and organization sponsors.

You can get discounts on their products

and services using the code

YonEarth,

all one word with a Y.

These sponsors are listed

on the YonEarth.org-support-page.

If you found this particular podcast

episode especially insightful,

informative, or inspiring,

please pass it on and share it with a friend

whom you think will also enjoy it.

Thank you for tuning in.

Thank you for your support

and thank you for being a part

of the YonEarth community.

0 comments