No products in the cart.

Aaron Perry

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C40PFWdcDcgu0026feature=youtu.be

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C40PFWdcDcgu0026feature=youtu.be

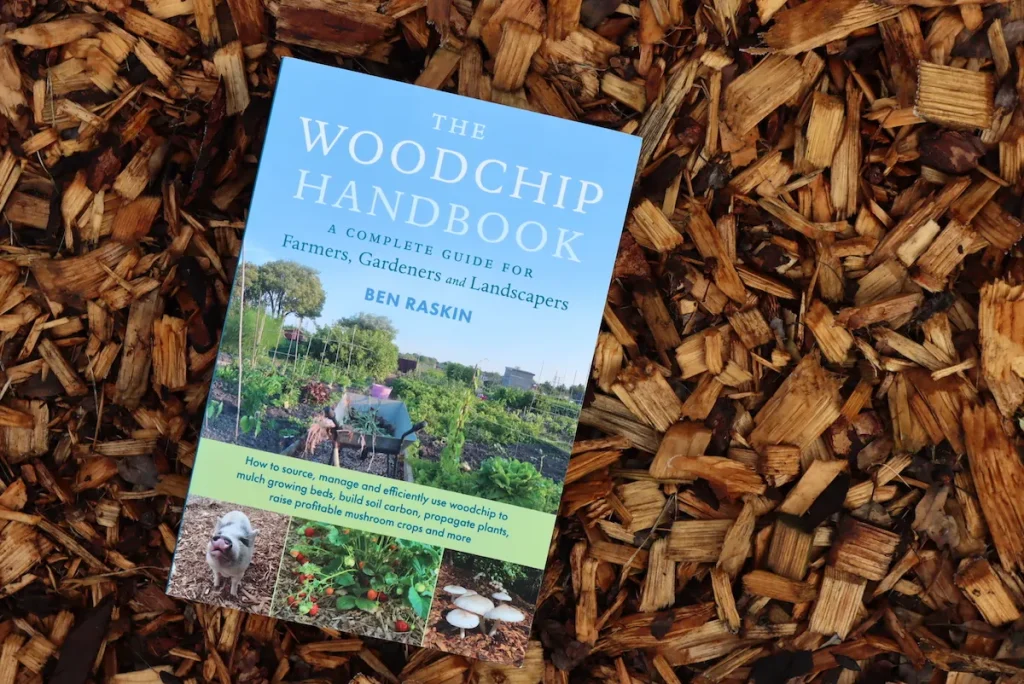

The Woodchip Handbook, published by Chelsea Green Publishing, is beautifully designed, and has striking color photos – it’s a must have for new and seasoned orchardists, silvopasturists, and agroforestry practitioners alike!

Use the code: YOE35 for a 35% discount on The Woodchip Handbook at Chelsea Green Publishing.

Ben Raskin has worked in horticulture for more than twenty-five years and has a wide range of experience in both practical commercial growing and wider policy and advocacy work.

As head of horticulture and agroforestry for the Soil Association in the United Kingdom, he provides growers at all levels of production with technical, marketing, policy, supply chain and networking support. He is currently implementing a 200-acre silvo-pastoral agroforestry planting in Wiltshire, England.

Ben is the author of several previous books on gardening, including Zero-Waste Gardening (2021) and The Community Gardening Handbook (2017), as well as three volumes of the “Grow Together Guides,” aimed at families with young children: Compost, Grow and Bees, Bugs and Butterflies.

Additionally, Ben co-chairs the Defra Edibles Horticulture Roundtable, and sits on the board of the Organic Growers Alliance and Community Supported Agriculture Network UK.

Facebook: Ben.Raskin.5

Episode 003 – Brook Le Van, Sustainable Settings Biodynamic Ranch

Episode 070 – Jeff Moyer, (Former) CEO, The Rodale Institute

Episode 089 – Yichao Rui, (Former) Chief Soil Scientist, Rodale Institute

Episode 095 – John Liu, Founder, Ecosystem Restoration Camps

Episode 098 – Lin Bautze, Goetheanum Section for (Biodynamic) Agriculture

Episode 123 – Marissa Pulaski, Co-Founder, Drylands Agroecology Research

Episode 124 – Nick DiDomenico, Co-Founder, Drylands Agroecology Research

(Automatically generated transcript for search engine optimization and reference purposes – grammatical and spelling errors may exist.)

Welcome to the YonEarth Community Podcast. I’m your host, Aaron William Perry. And today we’re visiting with Ben Raskin, the author of the wood chip handbook, a complete guide for farmers, gardeners and landscapers. Hey, Ben, how you doing?

Well, Aaron’s great to be here. Yeah, so so excited to chat with you today about one of my very favorite topics, which is soil building and mulching and so on. And you’ve got a whole lot of very specific and practical knowledge to share with us today. So I’m really happy we can have this chat together.

Yeah, well, wood chip is one of those things when I started writing it. People are like, oh, it’s a bit niche, isn’t it? And then when you start talking to people, I love it. I’m so pleased as a product. So it’s sort of, it sort of seems a bit, a bit specialist, but actually so many people are being interested in it. It’s been great.

Yeah, absolutely fabulous. I can see why after reading it. Ben Raskin has worked in horticulture for more than 25 years and has a wide range of experience in both practical commercial growing and wider policy and advocacy work.

As head of horticulture and agroforestry for the soil association, he provides growers at all levels of production with technical marketing policy, supply chain and networking support.

He is currently implementing a 200 acre silver pastoral agroforestry planting in Wiltshire, England.

Ben is the author of several previous books on gardening, including zero waste gardening and the community gardening handbook, as well as three volumes of the grow together guides aimed at families with young children, compost, grow and bees, bugs and butterflies.

Additionally, Ben co-chairs the defra edibles horticulture round table and sits on the board of the organic growers alliance and community supported agriculture network UK.

Ben, I love that you write books for both adults and children as do I as we discussed and we’ll chat about that in a few minutes.

But before getting into those topics, let us know, tell us why wood chips, why does this matter, what’s the big deal?

So I guess I like a lot of people, I’d use wood chips for mulching parks. It’s kind of quite common and it’s really good for that person.

I’d used a bit for mulching some plants, but I hadn’t really thought about it beyond that.

And over the last five or six years, really, partly because of the work we’ve been doing with the tree planting on the farm.

And partly because some of the trials I’ve been involved with through the work we do, the sort of association and the innovative farmers program that we run there and we’ll talk more about.

Just a number of things just kept on popping out. It’s like, oh, wood chips can do that and wood chips can do that.

Well, there’s a bit more to it than just sticking it on the pubs and stopping a bit.

You’ve been getting muddy really. So it was a sort of drip drip, I guess, in a way.

And then there was one big eureka moment, which maybe will come onto later. So I’ll leave that hanging maybe as a trailer.

I like it. Yeah, leave a little hook there for the audience. That’s great.

You know, reading through the book, which of course is published by Chelsea Green Publishing, one of our partners at the Y on earth community.

And I’ll just real quick mention that if you’d like to get Ben’s book, you can use the code y o e three five for a 35% discount at Chelsea Green.

And we’ll be sure to share some of the links and other resources a little later on.

But, you know, as I was reading through this, Ben, I was struck by the level of detail, the comprehensiveness of the book, including some of the science and more technical aspects.

But it’s laid out and organized and articulated in such a clear, straightforward, accessible way.

It seemed to me that this would be a valuable resource for just about any gardener, farmer, landscaper, as we mentioned in the subtitle.

And you’ve included a lot of really valuable information, you know, ranging from overall uses and benefits to what’s going on with nitrogen fixing and even getting into growing mushrooms and so on.

And I’m excited we can work our way through some of these topics, but before getting off course a little from the main points here, could you just tell us what are the overall uses and benefits of wood chips, you know, why should folks consider expanding their use of wood chips and their gardens and farms.

So I think, you know, not to move away from mulches, the mulches aren’t great and it’s still the easiest way, I think, to make use of wood chips.

And not just the weed control, but the moisture retention temperature modulation, pest and disease control, you know, there’s a whole range of quite unexplored benefits when you’re using anything.

It’s just keeping the weeds down, but it’s actually doing quite a lot of other stuff.

But then much more now, I’m interested in a long term effect on soil health from it.

And one of the, you know, a lot of the science that I that I use in the book, some of it came from David Granettstein who you may already have come across, who’s done a lot of work with commercial orchards in the space.

And he, he sort of shows the benefits to the tree and to tree health and to yield from using organic mulches and wood chip mulches as opposed to, you know, past people or herbicide weed control.

So that was quite powerful, you know, I’m quite steeped in the commercial world, although as you say, you know, these principles are applicable to anyone.

So it’s just seeing that commercial benefit made me made my ears print up in a way and go, okay, it was this.

It is quite expensive to put this stuff down commercially, but you get the benefit back.

So if commercial people are doing it, then there’s absolutely no reason why you know, if you’re doing it in your garden, there’s no barrier in a way, apart from getting hold of the stuff.

And then there’s a few other things. So there’s one girl that I that I quote quite a lot in the book in told us or told you, as he’s known, is a very long standing vegan organic grow it here in the UK.

He’s been using wood chip for I think 10 plus years and he’s mostly been composting it and spreading it onto his soil as a sort of help booster.

And and he’s, you know, his soil is just incredible and it’s not the greatest story. It’s not typical vegetable growing land, you know what he always says, I’ve got some good soil.

It’s just you got to find it in amongst the rocks.

There’s that kind of, you know, so we have this sort of soil classification system here in the UK.

They have grade one, which is the best, you know, which is really good or to cultural land and it goes back to and then three a and three B and I think he’s three B.

But he said, since he started using wood chip on his soil, he’s seen his productivity just shoot through the roof and his soil helps shoot through the roof.

And he’s done, you know, he’s had worm counts down on his farm and he’s got millions of worms per, perhaps, you know, tons of them under there.

And I remember going one time to see him and we he just spread the the wood chip a couple of weeks earlier and we were looking down at the soil floor and literally every piece of soil you can see was a worm cast.

It was it was astonishing. I’ve never seen this sort of peaving kind of the active mass of soil under your feet. It was extraordinary.

So it’s not things like that. You just, you know, you go, okay, there’s definitely more than just mulch.

And then he also makes his own propagation compost from wood chip.

And then there’s another grower for a monastery who used to grow for the Prince of Wales in our own business and he makes these hot beds out of wood chip.

So it’s a harnessing the heat as they rot down to to use for propagation and the spring.

So he allows loads of stuff other than just mulch or the hesitates they just mulch to this pretty powerful.

You know, I imagine most of our audience know what worm castings are, but just in case some might not just mention these are the the excretions of the worms as they’re moving their way through the soil.

As the tritivores, right, they’re eating a lot of the decomposing organic matter. And I understand that their castings have something like 106 beneficial enzymes in the those worms are providing so much bio available benefit to the biology of the soil. Is that your understanding, Bill?

Absolutely. And as well as that, they produce this kind of sticky mucus. And that’s really beneficial, but helping to create this aggregation of sort of the helping it sort of plump together.

And that gives us all resilience. You know, so if you get really heavy rain, which, you know, we are increasingly getting out of climate change.

The structure will be destroyed. And if it’s really hot and dry, it’s going to hang onto the moisture that’s in it more easily because it’s got these.

So, you know, all kind of matter full soil. So yeah, that, yeah, you definitely want, you definitely want words. I mean, I know they’re not native of it. I think some of them are native and safe. They are here, but you know, certainly we see them as beneficial.

So they’re an indicator of soil health. Certainly so.

Well, certainly the farmers and growers I’m connected to throughout North America and elsewhere all seem to agree that worms are very good to have around.

So I think it’s a general consensus as far as I can tell. Yeah.

You know, just hanging on the mulch topic here, I want to make sure we’re making one distinction that you make in the book, which is avoiding the artificially colored wood chip mulch.

Can you tell us a bit about this and why that’s not necessarily what we’re looking for?

Yeah, so it’s you’ve got to be careful. I think, you know, what I’m looking at is is chopped up trees. That’s that’s what I want. I don’t want anything else in there.

So I don’t want all pallets, which might have, you know, different stays one and I definitely don’t want any old painted doors or, you know, so there’s a lot of recycled wood that is sometimes good wood chip and you’ve got to be pretty careful not to get that on.

The colored ones, I mean, I honestly instinctively just I don’t like them very much anyway. I think they look a bit old.

Actually, when I looked into, you know, the potential arm from them.

It’s not quite as bad as I thought it was going to be. I think, you know, I think historically there was probably some quite nasty chemicals in them. I think now they tend to be.

So I mean, you’ve got to have fairly benign dies, but I just don’t quite see the point, you know, you really, you just want chopped up this tree really.

So say I would avoid any and decide which you effectively paying, you know, someone to have made it pretty color when you don’t need them to, you know, it’s going to be an expensive way of buying it anyway.

Yeah, and speaking about sourcing, you go into some detail around sourcing strategies that, of course, will vary depending on our location and our purpose, our intent, our scale.

And so on, can you give us a bit of an overview of what you’ve discussed there in terms of sourcing?

Yeah, I see. So I mean, you can obviously, you know, even on a very small scale, you can make your own wood chip and what I started doing.

I think this is almost kind of like the centropic agriculture thing where you’re sort of pulling everything down into the sort.

So when I prune a bush now in my garden, I’m going to go a little garden, but, you know, I chop it up with a pair of second tears and just spread it on the soil.

So rather than take it away and either burn it or, you know, send it off the local composting seriously, I’m just putting it back into the soil.

So you can do it even on a very small scale, but obviously that takes quite a time.

You can, you can hire little mulches, little chippers and mulches in to deal, you know, if you’ve got a bit more wood than you can deal with by hand.

Again, it’s sort of, it’s quite a lot of effort for a relatively small amount of wood chip, I would say generally.

But possibly still better than getting rid of it and losing that resource from the land.

Once you get up to a slightly bigger scale, you know, or if you’re taking a really big tree down, then it’s definitely worth hiring in a bigger wood chip.

You know, a machine that will just plow through it and exemplifies you’re there for hours, kind of feeding these little branches into the chip.

You know, it can take a lot of time with the big ones.

They’re relatively cheap to hire in, you know, depending on where you are again, you know, the semi, if you’re, if you’re a bit more isolated, then actually you can’t necessarily get hold of this machinery.

That’s an issue we had a, and it stays up in Scotland as you use the picture of his raised beds in the book.

And there’s just no one within, you know, 150 miles that hires wood chips.

So he had the add to buy one because it could lose just no option.

But generally, you know, if you’re near and there, then sense he should be able to get them.

And then if you’ve got more land, you know, if you’ve got your own small owning a farm or then you can start to grow your own.

And that’s, to me, where it hits the sweet spot, you know, you can get the benefits of having those trees and that short rotation pop is particularly.

So you get the biodiversity benefit, potentially win break benefits and all of that.

Browse if you’ve got livestock and then you get this great resource when you manage it.

Yeah, you know, we’re even hearing about some communities here in North America that are pulling together often with a local nonprofit.

To have the wood chipper resource and a trained crew to manage it that can go to different yards and neighborhoods when folks have need and opportunity to chip up wood.

So we’re actually working on a resource currently that will be out hopefully sometime in the next year.

So that is focused on neighborhood scale stewardship regeneration and sustainability efforts and, you know, helping move the needle in that direction.

So we’ll be sure to include wood chipping as part of this resource and.

There are a thing as well.

There’s a, there’s websites where you can sort of register yourself to receive free chip as well.

And I think in the States, the thing there’s some of the power companies when they clear the trees from the lines will sort of redistribute some of that chip to local, you know, customers or neighborhoods.

There’s, you know, there are opportunities to get hold of free chip in some quantity.

And certainly that’s what we did a farm where I work where we’re, you know, we have to.

Arborist who, you know, in the UK, you have to pay to get rid of your wood chips.

So for them to be able to give it to us, you know, one of them particularly is, you know, we’re a mile away lives down his way home.

You can just drive in, you’ve got a concrete pad, you can drop it off. It’s simple and it sort of works for both of us.

So, but yeah, I have heard in some parts of the UK now you can’t get hold of it free.

You have to pay them to drop it.

So I think it’s sort of it’s getting scarce in some parts.

Yeah, the old supply and demand, huh?

Exactly. But that’s, I mean, you know, okay, it’s a shame you can’t get it free.

It’s great that it’s being valued and I’m not just kind of done.

So, you know, because there was a time when it was ending up in landfill, which is just crazy.

Yeah, no doubt that’s, that’s doubly, if not triply, negative impact, right?

One of the things we would love to share with people and make sure our audience knows about this today is that when we send our organic, quote unquote,

waste to landfill, often they go into anaerobic decomposition, which produces a lot of methane that leaks up into the atmosphere exacerbating the energy heat trapping attributes of the atmosphere.

So whenever we can, with any of our plant derived, whether it’s use paper towels or kitchen scraps or wood chips, leaves in the yard, whenever we can compost those instead or apply them to the landscape.

It’s a much better situation overall. Yeah, absolutely.

So what about when folks are sourcing chips from commercial suppliers and or are buying them?

What’s the best way for people to get the quality they’re expecting and make sure there aren’t contaminants and these aren’t recycled wood products that might have paints or whatever on them?

Yeah, I mean, it can be tricky. I mean, the best way, obviously, is to know who’s producing it.

And again, you know, we’re lucky we’ve got these two guys and, you know, we can look at the bandwidth comes in and, you know, they know the sort of stuff we want.

Although, you know, we, we occasionally get, you know, chainsaw helmet left in it.

But yeah, generally the quality is great.

And I think, you know, you mostly you can see if you look at it, particularly if it’s not composted already, you can see whether it’s got anything undesirable in that, you know, you want nice clean bits of what looks like recognizable tree.

But, you know, ask us the retailer as good as you’re getting from and, you know, if it’s an arborist dropping some chip, you know, like the look of it and, you know, send it back because, you know, you don’t want it.

It’s not useful to you that it’s, you know, free is not always good is it? If it’s not something you want. So, but normally, yeah, normally you, if you look at it, you can see it once it’s composted, it gets a bit trickier.

Because everything sort of breaks down a bit and looks proud and unless you’re looking at it, it might be scary. You can’t always tell what’s in it.

Again, we have that, you have been a problem with some of our green compost or green waste compost. Sometimes I’ve got, yeah, the municipal ones, which are the home for a lot of glass and plastic contaminants in them.

But you can’t see it if you look at it often. So, you know, one of the things I like about wood chip is much less likely to have some of those in because it tends to just come from trees.

Yeah, makes a lot of sense. And you could just mention a few moments ago about, you know, for those who are able to grow your own and you mentioned a number of short rotation copies, species that are really useful, including willow, popular hazel chestnut, etc.

You describe for us why those particular trees have such a beneficial value in this kind of a wood chip system.

So I may be come on to willow in a minute, but generally I think there’s not very much research has been done on single species chip.

I think there’s potentially just so much that we could get from that because each tree will have a particular chemical makeup that might benefit, you know, our system in a particular way.

But most of that research hasn’t been done. And then within that you, you know, different trees, you know, some trees are hard.

You know, willow obviously goes really quickly, but it breaks down quite quickly and in one of our trials, one of the grows used the horn bean mulch, which was really hard and lasted three times the amount.

You know, you go, okay, well, I’m going to get less chip to plant a year, but if I’ve any got to apply it once instead of having to apply it three times, then it might still be worth it.

So it’s not understanding the, you know, the different properties of different woods is really helpful, but the willow is particularly interesting.

We did one of these innovative farmers field lands. I mentioned looking at willow.

So there’s a scientist called Glenn Percival, who works a lot with urban trees, and he was doing a trial using single species wood chip.

And he noticed that the apple tree that he put the willow chip around seemed to have less apple scab disease than the ones that didn’t have willow and thought that’s quite interesting.

And the theory is basically that the psilocacid, you know, the aspirin less in willow,

stimulates, seems to stimulate an immune reaction in the tree that makes it better able to fight off disease.

So we wanted to test that with some commercial alcohol excited producers here in the Southwest.

And we did, I think we had five or six years of thing involved in the trial.

And the trial showed a trend towards effectiveness. We didn’t prove it.

Mainly he thinks because they were all bit scared of putting enough mulch on because they harvest mechanically and they didn’t want the chip getting caught up in the machine.

So they didn’t put as much chip down as he hoped they would, but there was still a trend towards this reduction in disease.

And in theory that, you know, that should work on almost any diseases, creating effectively a more bust healthy tree.

So there’s stuff like that that is, you know, not explored very much, but I think as huge potential.

Very interesting. You know, we do a lot of work in the bio dynamic community worldwide and actually have one of our social enterprise products is called soil works of bio dynamic preparation blend we offer for sale and actually can offer discounts through the podcast here.

And I know that in the wine growing regions of California, for example, they’re using a lot of bio dynamics on both organic and conventional vineyards because it’s been one of the only things that’s helpful with the light that folks out in California have been dealing with for many years.

And I’m curious, are you seeing.

Vintners using wood chip as well on their vineyards is that something that is being done now at a substantial scale?

Not many. There’s one or two grows that I’ve been talking to that started experimenting.

It’s quite it is difficult on a commercial scale because it’s quite is costly. I mean, the material itself is not always that expensive.

But spreading it and particularly in a somewhere like a vineyard, you’ve got a lot of rows of a lot of small plants, you know, say it’s slightly different where you’ve got big trees and not so many of them.

But it’s, you know, even if you think it’s great and even if it’s having a difference, just getting them getting the material and spreading it is a big pot.

So, so this, you know, again, this is why I think if you can start to produce your own and have it on site.

And then you’re sort of cutting out some of that transport cost, which is the big issue really for a lot of it.

The material is usually free or cheap, but the cost of transporting it and spreading it is the barrier.

But yeah, it would be interesting to see how much effect it has on some of those in your disease.

Yeah, yeah, very interesting. And getting back to the point about harder woods generally breaking down more slowly.

Is it essentially kind of a one-to-one correlation in terms of the faster softer woods and the slower growing harder woods in terms of how long that wood chip lasts in contact with the soil?

I mean, instinctively, yes. I haven’t seen studies actually looking at breakdown rates.

And I think it depends a little bit on probably climate, you know, so things probably break down quicker here when we’re a bit warm and wet.

You know, whereas if you’re really dry, they’re just getting a lot of dry, they’re just going to sit there probably.

So, I suspect there’s that there’s the, yeah, I don’t know the shots.

I just know from looking at stuff and using it that there are definitely harder wood takes longer to break down.

Bigger lumps take longer to break down.

You know, so some of you are quite often get asked, well, what’s the best chip to use or how big do I want to have?

They’re like, spend what do you want to use it for?

Because it’s not big or small, it’s not good or bad.

If you want to mulch a tree, then you probably want big fresh chip.

Because it’s not, you know, the roots are beat down.

It’s not going to rob nitrogen or you know that it will rob nitrogen just from the sort of one or two centimeters and it touches of the soil.

So for a tree, you know, the roots are beat down as fine.

But if you’re starting to mulch, you know, so my rasp resource, the shallow root inventables and you put fresh wood on the surface.

It’s probably caused some problems that any might want.

I have a very small chip or you might want to compost it first.

You know, since I’m understanding, I guess what you need from the material will help to sort of get it in the right condition.

Great. Yeah, I want to ask you a bit about the nitrogen piece in just a moment.

But this makes me think I’m out here at Elkron Farm and in the in the gardens, we’ve got wood chips down in the walk paths.

Not only is this a wonderful way to keep the walkways covered and not so muddy when there’s rain, but it’s also delightful to walk on barefoot.

And this is a use that I imagine you might advocate for folks in all kinds of different climate situations.

Yeah, absolutely. I know a lot of people do is then at the end of the season.

So, in fact, you screened up the slightly composted chip from the path and put it onto the bed or the soil and then put fresh wood chips down on the path.

So it’s better than just starting that cycle of breaking stuff down already by using it as a, you know, the walkways.

Oh, it’s great. Yeah, and in the book, the Witch of Handbook, you’re also talking about strategies around nitrogen specifically in nitrogen fixers.

Can you walk us through that what you advise there?

So, yeah, and again, this sort of for me, a lot of this comes into holistic farm planning.

So, you know, one of the one of the things I think this held.

Would you back a little bit over the years is the reputation it has for locking up nitrogen and everything.

Would you want to go look at nitrogen?

And yeah, as I said, you can do that and you can you can do it really badly if you get it wrong.

But actually, the risk generally I think is pretty low.

And I think the problems come over when you use it for shallow region plants, as I mentioned earlier, or if you dig in fresh wood chip, that’s when you really get problems.

So, so where I mentioned before what what seems to happen.

So, so when wood starts to break down, it’s the fungi that are breaking it down.

So, bacteria can’t really start that process.

They’re not strong enough to get through the complex ligaments in the wood chip.

So, it’s the fungi that starts it.

And they actually have a relatively low nitrogen need compared to bacteria.

But they do need some. They need a better nitrogen to work and function.

And if there’s no nitrogen in the chip.

So, and again, the amount of nitrogen will depend on the age of the woods that the chips made from.

And we’ve made come on to rain your wood chip, this kind of younger wood chip.

But effectively, you know, if there’s a lot of bits of leaf and young bark in the chip, it will have more nitrogen.

And therefore, less likely to lock up nitrogen.

If it’s from a big old tree, you know, you imagine that whole trunk is just carbon basically.

There’s not much else.

And to break that down is going to need some nitrogen.

So, what happens if you just spread it on the surface is.

The bits, the fungi there kind of looking for nitrogen has a bit that comes down in the rain, but most not very much.

They’re going to go up looking for it and scavenging it.

And they’re going to hit the soil and they go, there’s a bit of nitrogen here in this top layer of soil.

So, they kind of grab that and use that to start breaking down the wood chip that’s touching it.

As far as I can see, they don’t go much deeper than that.

So, if you just lay on the surface, you’re not going to get probably most of the time.

If you then dig it in, every bit of wood chip is then surrounded by.

Soil and it’s going to suck nitrogen from every bit that it’s touching.

So, if you dig it down the foot, you’re locking up nitrogen at the top of the soil.

So, that’s why you really don’t want to dig in.

I mean, I tend not to dig an even composted wood.

I tend to put it on top and let, you know, the worms and other things pull it down.

But definitely with fresh wood chip, you want to keep it on the surface.

But obviously, it’s a temporary, so it’s a cycle.

So, it’ll suck that nitrogen up to start with.

But as the wood chip breaks down, it releases it back into the soil and then it’s absorbed.

And because you’ve boosted, you know, worm populations, funky populations, all of this stuff.

It’s locked up and it’s until you’ve got this reservoir of, you know, nitrogen,

but actually the whole load of other nutrients.

And if you then, you know, if you start producing your own and maybe using something like older,

which is nitrogen fixing anyway.

So, you’re then effectively pulling nitrogen out.

You’re getting some nitrogen anyway from the tree.

You’re then chipping what is on a short rotation cop is quite a high nitrogen wood chip relatively.

So, then you’re kind of really starting to build fertility and I’m really interested in how we.

How we use those sort of more permanent type of crops for building fertility.

You know, we’ve had a tendency to go.

We’ve had animals to do it and, you know, you’ve had lots of green stuff in there.

And actually, I’m not sure you do.

If you take a slightly longer view and build it in around a longer rotation and a longer system.

Yeah, so, so interesting.

And speaking of animals and speaking of fungi.

I want to be sure to ask you about both growing mushrooms and.

A little pasture and agro forestry strategies that might be in use in certain.

Situations and settings.

Can you walk us through a bit maybe starting with the mushrooms and then get into the.

Yeah, I mean, I do, I do have to sort of issue a slight disclaimer on the mushroom.

I am no mushroom expert.

It was it was something that Chelsea Green and I decided we should cover in the book because it’s sort of.

You know, they grow so well in which it’s safe and I have done a little bit.

But I definitely would not want to set myself up as any kind of mushroom growing expert.

And, but it, you know, it’s a great medium for growing stuff.

The, you know, I read this.

When my first draft of that chapter, I, I sent to an associate here.

He’s a commercial mushroom.

And he said, yeah, you might have been a little bit optimistic about some of some of those methods.

I think the risk, particularly when you’re growing outside the risk of sort of contamination by different species.

The amount of time it takes to manage it.

So I had these sort of dreams of being able to, you know, inoculate my wood chip under my trees and suddenly I’ve got this free crop of mushrooms that are just going to spring up and.

And like everything I think, you know, you’ve got to know what you’re doing and be a bit more focused and really understand it.

You know, I have grown some some nice crops of things for very mainly in wood chip bags.

And it’s worked quite well, but I think to do it better, you’d need to either sterilize the wood chip or, you know, sort of.

Manage it in a more controlled way, which I don’t have the capacity to do where, you know, where we’re working.

But, you know, I think I think this huge potential and again, you know, looking at some of those single species wood chip, you know, definitely got the impression with my research that there’s some species that do really well on particular species.

I mean, some will only live on one particular species.

And some will grow on logs, but by chipping it up sometimes you can speed up the process.

It’s going to be kind of half digested there dinner for them.

So you can, you can sort of get a crop more quickly.

So yes, and that’s the mushrooms.

But the, the silver pastures is, I mean, that’s where a lot of my work at the moment is inspired, actually partly by Steve Gabriel, another Chelsea green author who came over and did an event for us as well as that four or five years ago.

So the farm I work on the whole farm is actually 1500 acres and we’ve been focusing the planting initially on 200 acres, although we’re now expanding a bit.

And it’s mainly an arable and livestock farm and a bit where we’re doing a lot of the tree planting is heavy clay and not that suitable for cropping, although we do do some.

And so we’re really interested in how we can maximize the.

Well, a range of things actually, so we’re looking to Helen Browning owns the farm business.

She’s the chief exact for sort of the association, but she’s also a farmer and her motivations were around climate change resilience.

You know, you know, we’ve got this wet heavy clay.

You know, it can grow crops, but it’s often too wet to get in and cultivate you get these really short windows in the spring when you can get them doing anything with it.

The there were too far away from the main dairy building, so we mostly have.

the young stop there, the young dairy stop and because it’s heavy and wet you know we’re limited

on the amount of time they can spend out there. We’re all saying it hasn’t passionate about animal

welfare so you know in some of the summers we’ve been having recently you know and you see these

poor animals aren’t filled with no shade you know so we’re looking at how do we drink shade,

how do we drink shelter, how do we dry the soil up there, how do we lengthen the grazing season

and we know that by reducing you know producing wind speed cream these little microclimates

the grass will grow earlier it will grow later so potentially we can extend the grazing season

by two or three weeks each and and then you know the other big thing is around providing

browse for cows you know in mostly cows in our instance but you know any animal really

and and we sort of we slip somehow into kind of cows eat grass or you know either

worsy grain you know so but actually you know cows can have something like 55% of its diet

can come from tree grows and an historically we’ve gone all the cows are eating the hedges

could get them away from the hedges rather than going well no let’s have more hedges you know

they wanted that much but it’s probably good for them so so we’re trying to incorporate as much

as we can into the system you know mostly for shade I would say but also to try and include the

browse you know there’s tree browse has higher micronutrient content than than a lot of forage species

it has higher tanning content so it can reduce internal parasite burden

you know there’s lots of benefits to having that and and again you know one of the

um the myths that I’ve sort of spend a lot of my time trying to bust is this sort of idea

that you plant trees and you lose your forage you lose your grass you know a lot of farmers

no and I can’t plant trees I won’t have any grass for cows and obviously you do have a temporary

problem in that while the trees are establishing you’ve you’ve kind of got to keep them away from that

tree but long term you know most forage species actually grow better in partial shade than they

do in full sun there’s a great study I can’t remember if I put it in this but it’s in I

added another book called the agroforestry handbook which there’s a great study where they looked

it’s like 45 species of forage and they grew them at 50% shade 80% shade 100% shade or something

like that and not 100% shade that would be nice anyway the different kind of level of shade

now basically all of them grew better uh sort of 40% 50% shade and and a lot of them grew better

even 80% shade than in full sun and so it’s a having this sort of mix of of trees and forage

can be really beneficial for everything you know not to mention that biodiversity benefit of more trees

that’s wonderful yeah we uh out here at Elk Run Farm there’s a whole cluster of farms converting

open pasture into silver pasture agroforestry systems which here in the semi-air and west is also

a really important part of the water management strategy it helps a lot with infiltration and

better water retention in the landscape so it’s it’s great to hear about this and yeah this

agroforestry handbook I imagine is a good resource for folks who want to dive deeper into this

particular topic yeah and I mean it’s um unfortunately we no longer have any hard copies left but

it is available to download from solid association website people want to get hold of it okay yeah

uh what what’s the website by the way we may as well include that uh my website or the

solid association website yeah so yeah I think it’s just the solid association dot oh my guess I

mean based google the solid association it’ll come up yeah good good good little agroforestry handbook

excellent yeah and we’ll be sure to confirm that and include that in the show notes when we publish

the the episode and by the way on that note Ben let me uh remind our audience this is the

YonEarth community podcast I’m your host Aaron William Perry and today we’re visiting with Ben

Raskin the author of the woodship handbook and you can connect with Ben via Twitter at Ben

underscore raskin r-a-s-k-i-n uh he administers a Facebook group called woodship for soil health you

can join that if you’re interested uh and of course Ben has his own website BenRaskin.uk um

there’s also a Facebook page called agroforestryuk you can check out and on instagram it

is Ben L Raskin for his middle initial Leo um and I want to be sure to reiterate that uh his book

woodship handbook is published by Chelsea Green publishing one of our partners uh if you haven’t

yet been to the YonEarth.org website you can check it out and go to the partners and

supporters page and you’ll find Chelsea Green there along with a number of other wonderful

companies and organizations we collaborate with with Chelsea Green in particular you can use

the code y-o-e-3-5 for a 35% discount on Ben’s book and all the other offerings they have at Chelsea

Green and you can get to this via our partners and supporters page or just go to Chelsea Green.com

want to give a shout out it as well the purium organic superfoods they’re offering $50 off of

your first order when you connect through YonEarth.org earth hero safe and sustainable

household products and more uh similar discounts and specials there and then of course I mentioned

soil works our in-house social enterprise offering biodynamic soil preparation special discounts

there uh for you on soil works and whale waters are biodynamically and regeneratively grown hemp

infused aromatherapy soaking salts if you haven’t tried whale yet for your health and wellness

give it a go it’s a great way to soak and enjoy and relax and uh yeah we’re just launching our simple

gardening wisdom video course recorded here at Elk Run Farm with Nick D. Dominico on a variety of

specific and simple strategies and techniques you can incorporate into your own garden and yard

and neighborhood we’re selling that for $33 discounted from $99 uh right now the month

of uh may and perhaps beyond may and a special shout out to our ambassadors who are part of our

growing global network and who are in our monthly giving program if you haven’t yet joined the

monthly giving program you can do so clicking on the donate button at YonEarth.org

and if you give it a certain level we’ll be happy to show you some whale water soaking salts on

a monthly basis as a thank you um and so yeah let me uh I wanted to mention too with growing

mushrooms I played around for years then um up at sustainable settings one of the big biodynamic

ranches here in Colorado and elsewhere where I was inoculating wood chips down I was inoculating

around existing clusters of cottonwoods I even was inoculating some uh straw bales and

got little flushes here and there but I found the uh best luck I’ve had at least in this region is

with the garden giant mushroom I forget the Latin name on wood chips around the garden it seems

that that one really uh enjoyed that and I understand that species of mushrooms of particularly robust

soil builder when it has the wood chips to work with I think that was off of a cotton wood chip

I don’t know if you see the garden giants out in your area of western England I did yeah I did

we’re doing the the Latin name and it sounds quite like the ones that I was growing but yeah

yeah and and by the way tell us a little about where you’re located right you’re explaining to

me before we started recording that uh you’re on the western edge of England not too far from whales

tell us a bit about the landscape there yeah so I well I live in officially live in the west

country uh which is sort of the west the south west of England which is which is where I’m growing

from a town originally from a tankel bell which is relatively famous so there’s got room and bags

there um I mainly about uh about sort of uh what I know about 25 miles from that um so it’s the

it’s the sort of easternmost part of the southwest so I’m actually sort of quite near the middle of

the south of England um but yes I’ve found a mile from from whales there’s a big bridge called

the seven bridge that you go across the river seven um into whales so uh yeah it’s it’s

uh what’s it like it’s rolling rolling countryside um so so when you’re in barf it’s kind of quite

steep hills like that um uh that I had to walk up to get to school uh where I am now it’s it’s right

at the southern end of an area called the Cotswolds which is uh sort of very you call it you know

if you sort of picture uh you know the English countryside post you know a little kind of chocolate

box villages there’s a lot of days about uh and the countryside is a bit more you know it’s sort of

yeah rolling you can see a bit in the distance but this is nice hill um traditionally sort of

sheetland um a lot of arable now um and then yeah that’s where I am sounds lovely makes me think

about uh Tolkien’s writings yeah yeah some of them some of the some of the the hills could be a bit

like that definitely yeah that’s so wonderful well I want to be sure to ask you um about another one

of my favorite topics which is Hugo culture uh Hugo culture and and I imagine some of our audience

is familiar but probably not everybody um this is another approach to working with the wood in our

soil building our garden our landscape strategies right yeah and I guess the future of that is you’re

not chipping the wood first mostly although you can include you know you can include chip wood into

the design but effectively yeah you’re varying big logs and letting them break down very slowly

as a long-term source of kind of matter how biology you know um and then reserves of water and

all the rest of it so yeah and there’s a really it’s a nice way of building resilience I think

into into systems um and I’ve not done it on any scale you know the interesting to see you know

tapping it tends to have been done on a relatively small scale but it would be really interesting

to see it done you know slightly larger commercial settings because I’m convinced the benefits um

and again particularly sort of you know you’re talking about water retention if you’ve got

slopes and you can build you know it’s almost like it’s kind of down with these logs that you

then cover with funfoss and soil and you know you can imagine them acting as you know as then

the words escape me you know when you catch the water coming down there yeah yeah yeah yeah yeah

yeah that’s great and by the way um in the book you mentioned the problem with peat

and and peat is something out here in the arid semi-arid Rocky Mountain West we don’t come across

very much probably the closest is for those who enjoy their peaty scotches after the workday

but you guys out there right have peat in the in the landscape at least in parts of the UK

and maybe you could explain for our audience you know what the kind of traditional historic use of

peat has been and why you know that is an ideal going forward so the effectively is this

long term buildup of moss in an effectively very anaerobic condition that sits

often in water most of the year and and it’s an incredible store of carbon you know holds more

carbon than grasslands and and thyruses is unbelievable amount of carbon and in islands they they cut

it and dry it and use it for fuel you know before electricity that was what heated you know a lot

a lot of Irish people used it to heat their homes and so there’s still a little bit of it is cut

for that but mostly what it’s used for now is for horticultural purposes for propagation

and for growing mushrooms actually commercially but from mushrooms and it’s it’s pretty cheap

because all you have to do is dig it up it’s it’s uniform it’s sterile it’s easy to use and it’s

pretty predictable as to how it’s going to behave I mean it’s not actually the best material in a lot

of ways you know it’s not it’s inert so it hasn’t got my biology you know it’s not always that

easy to to rewet when it gets dry but it’s not from a you know it’s cheap and easy and then

so it’s become certainly in the UK it’s become the default you know had become the default

material to grow seedlings and and I mean even you know people at one point I hope they’re still

not doing it but you know they spread it on their soil there’s a soil improvement which is it’s

hopeless for it disappears almost instantly so and as well as that the habitats where

the grows are often very unique they’re scientifically very diverse and special so you know you

start digging it all up and you’re destroying you know very sensitive side of their landscapes

so there’s been a growing movement over well I mean as long as I’ve been in horticulture

move away from it and it’s been hampered unfortunately by commercial interests and by the fear of

the unknown and we’re finally getting closer I think to a band here in the UK certainly for

amateur use but yeah the challenge we’ve got at the moment is the is how you transition you know

so in one sense there’s no reason why we should be using peat to grow stuff then did we

aim but you know for 99% of stuff apart from stuff that needs to grow and pee you know like

floods that come from areas that grow and pee you know most of it doesn’t need to be

but we’ve become so dependent on it there isn’t a supply chain around all of the other stuff

so you know there’s an increasing amount of peat-free material coming onto the market a lot of it

is rubbish it’s really really bad and so people buy it thinking they’re doing the right thing

and then you know it fails and they go well I’m not using that again I’m going to go back to pee

they’re worked so there’s a there’s a bit of a challenge it’s sort of how you get away from that

but you know one of the things that I discovered with with the wood chip and then we’re working

particularly with with the intolerance was it’s really easy to produce your own substrate from wood

you just need to let it rot there and it’s just time you leave it long enough and it will turn into

a really effective propagation media and you know you can stick it in a tongue bag in the corner

of your garden you know and just leave it for 18 months two years to the end of it and you know

put the big lumps back into a new pile and what you get out you can sell it now I haven’t tested

every single seed so there might be some vegetables that don’t do so well in it or that need made

you know this is where this single species could come in where you might find that

I don’t know hazel works really well for a particular crop and something else works better

for another one but certainly the trials we did so we did again we did an innovative

farm is field lab which looked at Tali’s homemade wood chip compost versus the leading

commercial peak compost and there was no difference in germination or performance in the crops

you know and any basically just stuff which is in a pile for 18 months 10 to the occasion in

15 so yeah and it’s really available you know it’s relatively freely available as a beef stock

which some other thing does so interesting let me mention too that after our main podcast interview

recording we’re going to record a shorter behind-the-scenes segment that our ambassadors have

access to and if you’re not yet an ambassador and you want to get access to these additional

resources you can go to the become an ambassador page on the yonors.org website and we’ll be

exploring some of this a little further Ben when we do the behind-the-scenes segment and of course

I want to be sure to follow through on our promise about the eureka moment that that you mentioned

at the beginning of the interview but before we go there I’m curious do you have a favorite

species of wood that you work with when you’re woodshipping? That’s a good question can mostly I

just get what the tree surgeon gets me so most of my wood chip is just a mix of stuff some of

it recognizable some of it not so I don’t know if I do but I do I mean I do love horn beam as a tree

I mentioned horn beam earlier with this with this child with the and then the mulch under the

under the apple trees with this horn beam and this guy so lovely dark color and it

held its form more so I don’t know yeah I’ve got a concept really got free I’ve doesn’t have

enough experience of different single species chip but I’m intrigued by the power of

willow I have to say you know it does seem to be this kind of just super life giver you know there’s

something pretty special about willow yeah I like willow also well what’s the the big eureka

moment that you heard yeah so it came out of an accidental experiment I love accidental experiments

is you find that stuff that you didn’t know you were looking you were looking for so we we’ve

gone area of the farm where there’s a little brook that runs alongside the field and we’ve got

some big ancient willows that were growing there and there’s a historically a lot of these willows

would have been pollotted and the trees would have been probably fed to the livestock or

you know used the fuel or something like that but because you know perhaps to the change

nobody really pollards commercially or for use anymore so so a lot of these pollards end up

getting neglected and grown out and there’s a grounds at the moment in the UK to which paste

farmers to pollard them so to effectively manage some of these trees particularly along with banks

so we just pollarded around 70 of the really big trees and had a lot of willow chip and in one section

we just planted a new area so this was in the sort of winter of 2017 2018 which in the UK 2018

was a really hot dry year I don’t know if it was for you but and and so we we threw the chip over

the fence with the intention then of me moving the chip and mounting a lot of the trees within

there’s just sort of a couple of acres of planting that we had and you know as often happens on

phones you know other things were more of a priority so I never got back to move the chip

so this one area by the fence has a mulch two and a half foot deep of willow chip

which you might think is probably you know almost too much it’s not a debt but I would normally

recommend but that year the trees that you know didn’t get a mulch barely grew I mean actually we

lost probably 50% of the trees that we planted in that in that year but this group of trees that

got mulch just grew phenomenally and within two years the trees that hadn’t got mulch were barely

passed my waist and the ones that had the mulch were 12 14 feet high and there’s a there’s a

picture in my book you can you know you can see and you can’t believe they were planted on the same day

and I think you know probably in that year it was around moisture retention I think you

know there was just the ones that didn’t have the mulch were just too dry and these ones did

them might have been a temperature thing as well so you know the mulch will keep the soil cooler

in the summer and warmer in the winter and say you know with that much mulch it’s possible that

the roots were just that much warmer over winter and so they just did did better but I think

that probably a lot of it is around moisture but but that you know that was the moment where I

realized we had to mulch every tree we planted and mulch it properly and and we’ve seen so we’ve

planted a couple of hedges last year which again was not as bad as 2018 but it was hot and dry for

us again you know we we had a period I think of about two months without rain which is you know

very England is pretty artificial and and pretty much every plant in this age survived and then

we lost 40 trees over you know 400 metres of hedges because we gave them 25 centimetres a

nearly a plus of mulch and it’s all broken down it’s only that deep you know sort of why it’s

broken down to an inch or something but you know so it’s but but it just protected it while they

established it kept them cool it kept them moist the trees have got away once they’re established

that’s fine that you know you don’t need to do it once if you do it properly and that was the other

thing for us we you know we initially we go we’re just printing around and but then it disappears

and it hasn’t done anything you’re gonna go back the next year and do it again and that’s you know

more than twice the cost so we’re we’re actually starting to slow down our tree planting a little bit

so rather than go we’re gonna plant everything we’re gonna plant it now and you know again now let’s

plant you know we’re we’re almost limiting our planting by how much woodchip we’ve got to

mulch the trees you get okay how many can we manage this you know that’s that’s my age

is to get right that’s our research that they’ll we’ve just roughly how many trees do it right we’ll

plant that many trees and we’ll make sure that they’re mulched and we can’t irrigate you know we

don’t have for most of our fields we can’t get water out of them so we have to plant them well and

get lost about it yeah imagine this is going to have application out here with a lot of the

agroforesty projects around here and I want to I want to just show our audience who are looking

at the bottom yeah photo it’s striking I mean in this video you may not even see on your I guess

it’s left the little trees that didn’t do nearly as well yeah so the ones on the left you can barely

see them yeah and then the ones on the right here for off of big trees yeah yeah there’s so

many wonderful color photos in the book too I want to be sure to mention that to to our audience

and be sure to encourage folks to get a copy of Ben’s book the woodchip handbook and Ben wanted

to ask you also can you just tell us a little more about the work you guys are doing at the soil

association and some of the other organizations that you’re connected to and helping to lead

yeah sure so the soil association is well I’ve been there 17 nearly 17 years which kind of seems

almost impossible I was only supposed to be there two years and I never left so we’re a

student farming charity probably the closest you’ve got is the road ends to you I would guess

but we don’t do the research side there’s a set for organic research organizations

and we we also have a certification business so we’re you know one of the main

certifies in the UK for organic farms and businesses I work on the charity side so I sort of

coordinate the woodculture and agriculture we work with the charity state I think as you

mentioned in the setup you know lot that is about supporting our growers it’s about by the way

the worst I’m gonna think about in separate to the agriculture bit is we have sort of three

three ways I work with growers and farmers like you know the ones are already organic to

certify we try and support and help them feed better the ones that you know we’d like

to be more organic farms so we you know we try to encourage people to certify and to you know

to to be organic but we also work with a lot of farms that will never be certified and you know

I’m interested in being certified but we we like them to be more you know organic with a small

sustainable originative or whatever you know term you want to use so you know there’s the change

in the farming landscapes since I started is just I mean it’s astonishing you know the 30 years

ago when I started you know you say you’re organic and you know it’s kind of dismissed and you’re

a bit of a lenient yeah well you know you’re not a proper grow or a farmer you know you’re just

just going to be a weeded deal you know and now you know everybody is on that part or you know

almost everybody that’s a tall board thinking and it’s just it’s fantastic so yes I do not

that and then work with you know as you mentioned policy and a lot of communication stuff

so you know we don’t have a particularly supportive government in terms of organic and regenerative

farming possibly getting a little bit closer but yeah so that’s always a bit of a bit of an

output struggle but the the agroforestry bit is is again it’s just joy for at the moment everybody

you know everybody agrees we should be planting more trees and it’s just kind of helping

again helping mainly helping farmers to identify their objectives and give them more information

and access to you know inspiration and case studies and things like that so yeah and then yeah so

you ask about the other organisations but I did feel a slight fraud because I’m no longer co-chair of

the that group that you’ve been to the death group but I’ve stepped down from that and I’ve also

stepped down to the organic growers alliance and boards which I was on for a number of years but

they’re a fantastic organisation you know getting a small independent organisation that supports

organic growers and you’ve got about 400 members I think and then the community-supported agriculture

network is something that I’m still very involved with and again I know it’s sort of there’s a lot

in the in the states as well we’re we’re catching up really here I think this we’ve got around

200 and also community-supported agriculture farms but it’s it’s increased massively over the

last you know two three years and and I think as people start to question you know traditional

supply chains and again here in the UK we’ve got very dominant supermarket multiple retailer

sector they you know they’re going tend to treat growers very fairly they’ve been underpaying

them for the number of years and some of their supply chains are starting to run into problems

and we’ve had shortages and people are going oh where am I going to get my food problem I just

expected it to be on the seed market shelf but what’s going to have to know and again you know

building those relationships with your with your grower and I have in that much closer commitment

I think a lot of people are seeing that as a really positive thing so that’s wonderful you know

in my book why on earth I spoke about a three-pronged strategy for our own food resilience which is

uh show no grow and it means grow some of your own however much you can even if it’s just a pot

of herbs whatever um and then know your farmers and sources for food to the extent that you’re able

and then show when it comes to sourcing from folks we don’t know personally of course the third

party certifications around organic regenerative organic fair trade of many of these wonderful

practices you know it’s those third-party certifications that really help us to know um and show

what’s going on so uh appreciate that and since you mentioned Rodel I have to shout out also to Jeff

Moyer and Yichau Rui two different podcast episodes we did with those wonderful guys at Rodel

Institute and I understand I neither of them are there any longer they’ve both moved on to

other things so it’s interesting how fluid some of this can be and I imagine your retirement from

deaf-run organic growers alliance means that you’ve you’ve left a really good market impact at those

organizations and uh it’s it’s so great to hear from you Ben and hear your depth of experience

and expertise and I highly encourage folks to get a copy of the woodship handbook from Chelsea

Green publishing and Ben you know before we sign off our recording here I want to just invite

you if there’s anything else you’d like to share with our audience uh that you haven’t had a

chance so yet of course we’ll do our behind the scenes here in a little bit but uh to conclude the

podcast if there’s anything else you’d like to share please uh the floor is yours oh I don’t know

I mean the one thing we’ve got I’m organizing a massive show a massive debate a massive show

September the agroforestry show we’re calling it so I hope you get thousands people now I

realise it’s quite a long way to come from the States but if anyone happens to be in the UK at the

beginning of September and what’s there you know wants to come see the farm so it’s based at the farm

where we’re planting trees we’re working with the Woodland Trust which another great uh organization

in the UK um and it’s yeah gonna be pretty exciting so that’s uh taking up a lot of my

head space and time at the moment is working for itself that sounds really exciting cool yeah we’ll

be happy to to share that and uh yeah with that Ben thanks so much for for joining me this this

day for this recording and it’s been a pleasure chatting with you uh really appreciate it and

on behalf of the wine owners community thanks so much for sharing so much with us about

woodshipping and beyond that’s been a real pleasure thanks very much to have a meal

see you then bye

the wine earth community stewardship and sustainability podcast series is hosted by

Aaron William Perry offer thought leader and executive consultant the podcast and video

recordings are made possible by the generous support of people like you to sign up as a daily

weekly or monthly supporter please visit YonEarth.org backslash support support packages start at

just one dollar per month the podcast series is also sponsored by several corporate and organization

sponsors you can get discounts on their products and services using the code y on earth all one word

with a y these sponsors are listed on the yearth.org backslash support page if you found this

particular podcast episode especially insightful informative or inspiring please pass it on and

share it with a friend whom you think will also enjoy it thank you for tuning in thank you for

your support and thank you for being a part of the YonEarth community.

0 comments